Shaking Hands with Other People’s Pain

“Nous n’avons pas toujours assez de force pour supporter les maux d’autrui.”

LA ROCHEFOUCAULD (1613 – 1680)

Here’s the trouble with solidarity, altruism, compassion, brotherhood and other values we often pay lip service to, while practising them so shabbily: it isn’t always easy or pleasant to join in a common struggle with some human being or community who is suffering a terrible fate. As the French moralist said: “We don’t always have enough strenght to bear other people’s sufferings.” (La Rochefoucauld) Let’s not idealize human beings: egotistical as we so often are, we would rather turn a blind eye to other people’s pains and keep paying attention only to our tiny little selves. Human as I am, when confronted by events that would disturb my peace-of-mind, like these who are flooding the news during the last weeks, my first impulse is to run for cover in the comfort of blissful ignorance. Why should I care if the Israeli army is bombing Gaza to a heap of ruins? Why should I look at the photographs of dead babies, injured women, dismembered elderly? Why shouldn’t I be allowed to choose the easiest path and retreat from these horrible occurrences, refusing to acknowledge their existence? Am I to blame if I’d rather act like an ostrich that hides its head in the sand?

Voltaire (1694 – 1778) once said that “every one is guilty of all the good he did not do”. That sounds to me a much more courageous and demanding statement than the one quoted in the epigraph. La Rochefoucauld’s phrase sounds like someone who uses a personal weakness to justify his choice of indifference. Voltaire wants us to take responsability on our hands and act on behalf of others; doing nothing may be sometimes considered a criminal cumplicity to the perpetrators of oppresion or genocide. La Rochefoucauld’s comment, on the other hand, seems to excuse a behaviour of inaction and voluntary ignorance and lassitude, when we’re confronted with “les maux d’autrui”. Myself, I can’t help but feel some contempt for the attitude of those who don’t give a damn about other people’s miseries and care only about their private little matters. My heart fills with admiration by people like Arundhati Roy or Joe Sacco, Simone Weil or Che Guevara (to mention just a few), highly sensitive and creative persons, who devote their life-works to shaking hands with other people’s pain. And acting in order to diminish human grief in our Samsarian planet (good planets are hard to find). Empathy, methinks, is a praiseworthy virtue, and one of the best definitions of it I know of is by Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara: “feeling anguish whenever someone was assassinated, no matter where it was in the world, and of feeling exultation whenever a new banner of liberty was raised somewhere else.”

Such thoughs have been fermenting in my mind during insomnias and daytime anxieties, as the numbers of injured and dead keep getting higher and higher in Palestine. But let’s not take numbers too seriously and forget the real heartfelt human suffering that numbers tell us nothing about. Let’s not allow our minds become numb with an overdose of tragic numbers. Each number is to be perceived as flesh-and-blood, as sentience and conscience, as beating heart and thinking brain, torn apart by war.

From a safe distance, I follow the news and they tell me a lot about other people’s miseries – “gunshot injuries, broken bones, amputees” (Sacco, pg 30). I feel powerless as I witness this horrors brought to me by Youtube, Facebook, Twitter, and the Blogosphere. I feel impelled to do something, even though I know quite well how little difference I can make by sharing Al Jazeera videos, sending to my friends the photos of demonstrations, or writing a post in a tiny little corner of the World Wide Web. A bitter taste of powerlessness and despodency nails me down to the chair as I witness the Zionists’ latest massacres in Gaza. Then I remember Voltaire and he inspires me to decide: the fact that one person can’t do much isn’t a reason to do nothing. If only everyone did this tiny bit, perhaps it would add up to something powerful enough to bring down from their bloody pedestals all these Masters of War?…

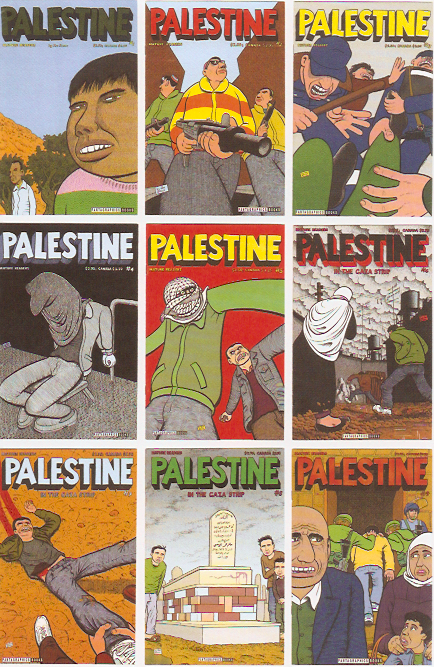

Sitting at home, far from refugee camps, I take a journey aboard Joe Sacco’s compelling graphic novel Palestine. Sacco takes me to see a re-presentation of what he himself has witnessed in Cairo, Jerusalem, Ramallah, Gaza etc. In Sacco’s pages, I see kids throwing stones against tanks and getting shot at by soldiers armed with M-16s and other hi-tech rifles. My brain fills with some sort of psychic vomit when I picture such scenes. If I had been born in Gaza, if I was a Palestinian kid, wouldn’t I be the one throwing stones against the invading army? Wouldn’t I howl in rage against these grown men in uniform who only speak the language of violence? Which language would I learn to speak, in such an environment, if not the language of precocious rebellious stone-throwing? And if my best friend’s life had been taken away from this world by a bullet in the heart, wouldn’t I be angry enough to, a few years later, join a jihadist group and become a suicide-bomber on the road to glorious martyrdom?

Unfortunately, there’s no end in sight for Intifadas, I fear, because no community will accept without resistance the sort of life conditions imposed by Israel in the occupied territories. Too many wounds have stirred too much rage, too much hunger for revenge, for any peace to be something reasonable to expect in the short term. Fuel keeps getting added to the fire of mutual hate. “An eye for an eye will make the whole world blind”, said the barefoot bald-headed pacifist Mahatmas Gandhi. But neither Zionists nor Jihadists seem to give a damn about Gandhi, especially when the wounds are fresh and the heart screams for vendetta.

Unfortunately, there’s no end in sight for Intifadas, I fear, because no community will accept without resistance the sort of life conditions imposed by Israel in the occupied territories. Too many wounds have stirred too much rage, too much hunger for revenge, for any peace to be something reasonable to expect in the short term. Fuel keeps getting added to the fire of mutual hate. “An eye for an eye will make the whole world blind”, said the barefoot bald-headed pacifist Mahatmas Gandhi. But neither Zionists nor Jihadists seem to give a damn about Gandhi, especially when the wounds are fresh and the heart screams for vendetta.

I can’t begin to understand how and when all this mess began. I look back into the past, trying to get a grip of the historical roots of the conflict, but History looks like a mad circus of chaotic antagonism. It seems to me that Israel was born as a consequence of one the hugest tragedies of the 20th century – the Holocaust. The Nazi’s III Reich almost wiped-out the Jews from the face of the Earth, and when Hitler’s regime fell in 1945 it was mandatory to find the survivors a Safe Home, in which they would be protected from ever having to be victims of such a mass-scale massacre. The “ideal” Israel would be a nation for the victims, for the survivors of that “Industry of Death”, to quote Steven Spielberg, which the Nazis set in motion in their collective psychosis of anti-semitism, racism, blind nationalism and totalitarianism.

But an old and un-answered question I’ve got is this: why should the Palestinians pay for the crimes of the Nazis? If Germany, infected by anti-semitic ideologies and imperialism, went on a killing frenzy against the Hebrews, why weren’t the Germans obliged, as the main perpetrators of the Holocaust, to offer some just compensation? Why shouldn’t Germany be made to concede, let’s say, one third of their territory for a Jewish State? Yeah: I see perfectly well that this solution wouldn’t work out. These neighbours, I suspect, wouldn’t live peacefully side-by-side with such monstruous memories of past bloody deeds haunting their coexistence. Despite the fact that Holy Jerusalem is considered a conditio sine que non by Jews: there’s no Israel without it.

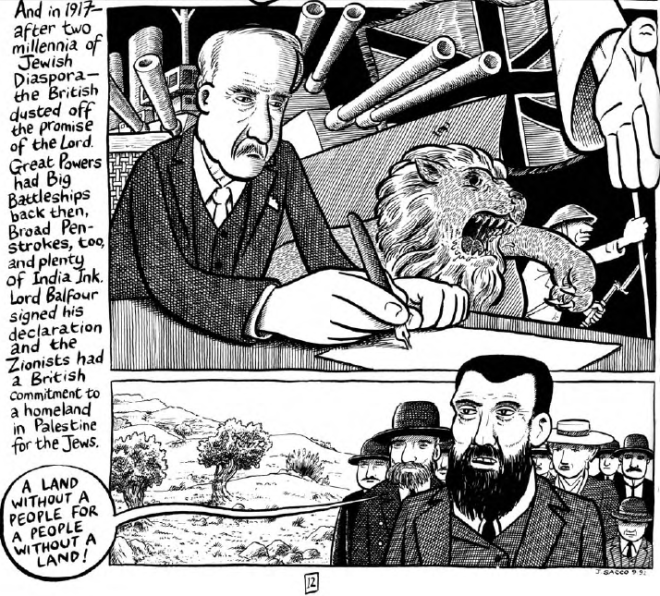

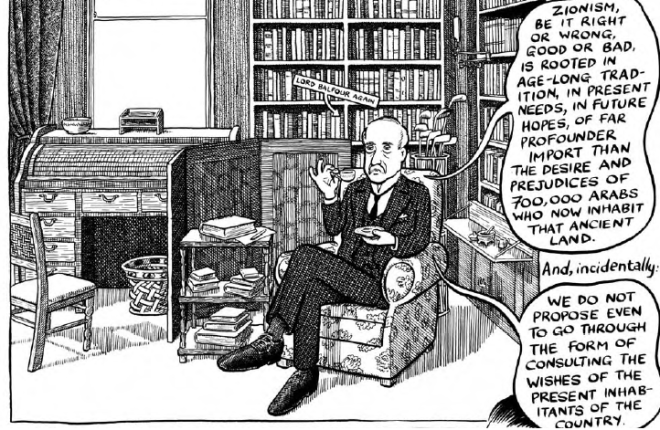

Reading about these matters, I also discover, in the works of Joe Sacco and Arundhati Roy, that the plan to create a Jewish state in Palestine pre-dates the II World War. In 1917, the English minister of Foreign Relations, Lord Balfour, signs a Declaration in which the British Empire makes a commitment to create a nation for the Jews in Palestine – a place which, according to a deceitful Zionist slogan, was a “land with no people for a people with no land”. Which, of course, is bollocks. Big time bullshit. At least 700.000 Arabs were living then in this land which the Zionists’s cynicism claimed to be a desert – and promised to them by God himself. But, as Bob Dylan sang in the 60s, “you don’t count the dead when God’s on your side”.

What awes me is also how yesterday’s victims can metamorphose into today’s oppressors. How was it possible that the people who survived the Nazi Holocaust became perpetrators of a new “Palestinian Holocaust”? What Israel is doing in Gaza – bombing schools, hospitals, UN-shelters; killing hundreds of babies, children, women, elderly, civilians… – isn’t this reducing a whole community to a status of Subhumanity? People in Gaza know today how it felt for Jews in Auschwitz to be treated as less-than-human and devoid-of-basic-rights.

What awes me is also how yesterday’s victims can metamorphose into today’s oppressors. How was it possible that the people who survived the Nazi Holocaust became perpetrators of a new “Palestinian Holocaust”? What Israel is doing in Gaza – bombing schools, hospitals, UN-shelters; killing hundreds of babies, children, women, elderly, civilians… – isn’t this reducing a whole community to a status of Subhumanity? People in Gaza know today how it felt for Jews in Auschwitz to be treated as less-than-human and devoid-of-basic-rights.

One could argue that Jewish experience in Europe was far from sweet and didn’t teach them much about gentleness between different cultures and nations. Pogroms, persecutions, concentration camps, gas chambers – these were some of the tragic cards the Jews were dealt throughout their wandering existence of chronic sufferers. In 1948, when they declared “Independence” and Israel was born, maybe they dreamt of Peace, finally? Anyway, if they did, the Dream has been shattered over and over again, for decades. There was never any peace. Israel is born into war and the nation’s first events, the first steps of this new-born child, have been tough as hell. Israel’s first breath was still sailing in the wind and the country was already dealing with the 1948 invasion from the Arab’s armies. After the defeat of the III Reich – who was supposed to last for a 1.000 years, according to the Nazi’s megalomania, but crumbled apart after 12 years – the Jews wouldn’t be allowed no peaceful retreat into well-deserved tranquility. They still felt endangered, they still feared annihilation, there were still enemies to fight. If they didn’t defend themselves, they feared that the Arabs would drown them all in the Sea.

I would argue that fear and violence often go hand-in-hand: a frightened animal is much more likely to attack than a tranquil, unafraid one. The human animal is also capable of bursting into terrible violence when he’s terribly afraid. When I look back at History’s madness, I see the Jews, after the II World War, trembling with fear and shocked with trauma. They had lost 6 or 7 million to the Nazi’s machinery of mass murder. And yet their survival instinct, their conatus (to speak in Spinozean language), was surely alive and kicking. To survive this tragedy they would need some radical means to establish themselves in some sort of safe spot. They would a massive Police State; one of Earth’s strongest armies; why not some atomic bombs? The U.S. would provide the means for Israel to become a military power whose self-confidence would be boosted by the possession of weapons of mass destruction. Israel, then, was born like a Bunker State, warmed to the teeth, with one of the world’s most rigid and paranoid Defense Mecanisms of any nation on Earth.

I would argue that fear and violence often go hand-in-hand: a frightened animal is much more likely to attack than a tranquil, unafraid one. The human animal is also capable of bursting into terrible violence when he’s terribly afraid. When I look back at History’s madness, I see the Jews, after the II World War, trembling with fear and shocked with trauma. They had lost 6 or 7 million to the Nazi’s machinery of mass murder. And yet their survival instinct, their conatus (to speak in Spinozean language), was surely alive and kicking. To survive this tragedy they would need some radical means to establish themselves in some sort of safe spot. They would a massive Police State; one of Earth’s strongest armies; why not some atomic bombs? The U.S. would provide the means for Israel to become a military power whose self-confidence would be boosted by the possession of weapons of mass destruction. Israel, then, was born like a Bunker State, warmed to the teeth, with one of the world’s most rigid and paranoid Defense Mecanisms of any nation on Earth.

But did they really believe they would build a safe haven in Israel after kicking out almost a million people from their homes in 1948? I’m sorry for my language: I’m quite aware that kicking out is not quite the right word. They did much more than kick out – they burned entire villages, they massacred entire populations, they created a huge mass of refugees, pushed very ungently, at gun point, into Gaza and the West Bank. Israel’s masterminds certainly don’t like this comparison, but this is how it feels to me: just like the Nazis deported the Jews from their homes and pushed them into the trains headed for the concentration camps, the Jews kicked out the Palestinians from their homes and pushed them into Palestine’s open-air concentration camps. Now it’s July 2014 and the world is asking in horror: is Israel applying the Final Solution? Is there anywhere or anyone in Gaza that isn’t a target?

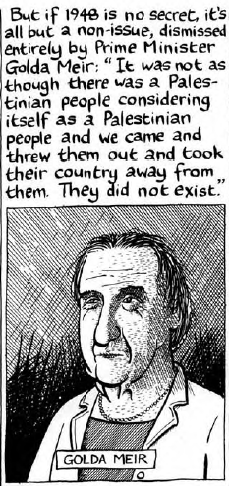

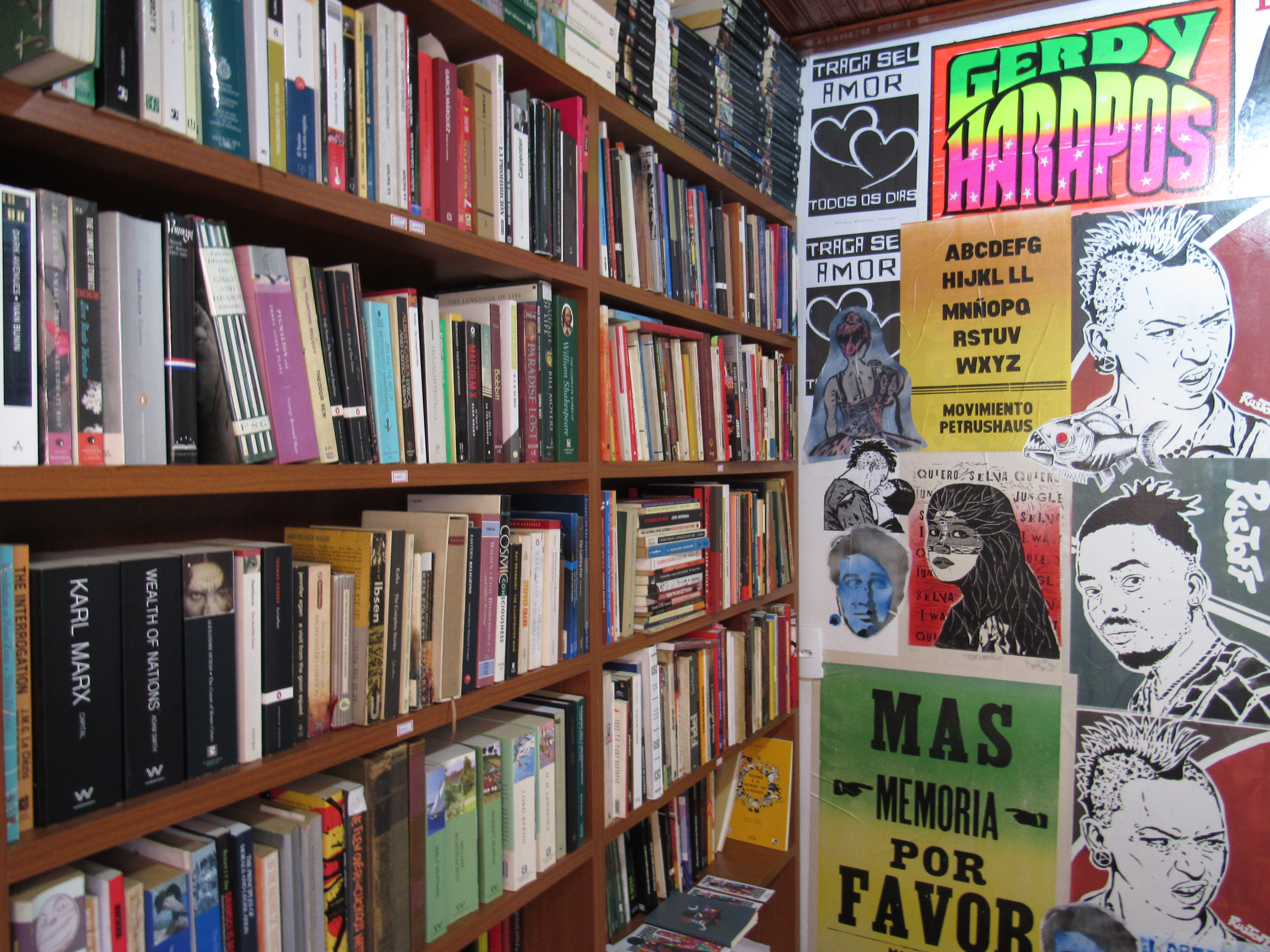

In the occupied territories, most of what we take for granted as civilization’s basic gifts to citizens simply don’t exist – right now, as you’re reading this, more than 1 million people in Gaza have no access to proper drinking water. Almost no one has access to electricity – especially after the only power plant in Gaza was bombed to ashes in July 29. In Joe Sacco’s book, I discover that, in the Palestinian schools, it’s forbidden by the Israelis to teach history or geography with any book that mentions Palestine – it’s not supposed to exist in the textbooks. Israel would like to erase it from the maps. Is Israel trying to accomplish in fact the lie that has been written in textbooks, that is, “Palestinians don’t exist”?

In a clinic, Joe Sacco meets two doctors who reveal that they see “a lot of respiratory illnesses from bad ventilation and overcrowding, problems related to political and social conditions” (p. 48). Life in Gaza and the West Bank can be quite cruel, unealthy, insecure, always threatned to end precociously. But the web of everyday violence is woven by acts of cruelty not only to people, but also to their means of existence. Joe Sacco draws, for example, a heartbreaking scene with decapitated olive trees, cut off by the Israelis, and then gives voice to the Palestinians’ suffering:

“The olive tree is our main source of living… We use the oild for our food and we buy our clothes with the oil we sell… Here we have nothing else but the trees… The Israelis don’t give people from our village permits to work in Israel… The Israelis know that an olive tree is the same as our sons… It needs many years to grow, six or seven years for a strong tree… Two years ago the israelis cut down 17 of my trees… my father planted those trees… Some of them were 100 years old… They obliged me to cut the trees myself. The soldiers brought me a chainsaw and watched… I was crying… I felt I was killing my son when I cut them down.” (Sacco, pg. 62)

This personal wound may seem tiny, but we need only to multiply it to get a picture of the collective wound inflicted by 120.000 trees up-rooted by the Israelis during the first four years of the Intifada. Besides the massive bulldozing of trees, Palestian homes were also demolished in great numbers: 1.250 of them were brought down to the ground during the same four first years of the Intifada; in the same period, no less than 90.000 Palestians were arrested and put behind Israeli barbed wire, watched by soldiers with their fingers on the trigger (Sacco, pgs. 69 and 81). All those who dared rise up against Israel were crowded into prisons, put into cages, treated not so differently than the Nazis did with the inmates of Dachau or Auschwitz. One man interviewed by Sacco remember the time he was arrested in an overcrowded tent, “a sort of hell”, “3×4 meters with 21 persons”, in which “the ventilation was very bad, just a coin-sized hole in the door for injecting gas in case of a riot.” (Sacco, pg. 84)

Eduardo Carli de Moraes @ Awestruck Wanderer

Toronto, July 2014

* * * * *

(TO BE CONTINUED IN ANOTHER POST…)

Recommended reading & viewing:

- Collective Punishment in Gaza (The New Yorker Magazine)

- ‘The world stands disgraced’ – Israeli shelling of school kills at least 15 (Guardian)

- Gaza’s only power plant destroyed in Israel’s most intense air strike yet – At least 100 Palestinians killed (Guardian)

- I also recommend following Al Jazeera & Counterpunch

[youtube id=http://youtu.be/4lsmFS75ed4]

Publicado em: 01/08/14

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes educarlidemoraes

comentários