Cheating death with a techno-fix: Concerning Czech sci-fi “Restore Point” (2023) by Robert Hloz

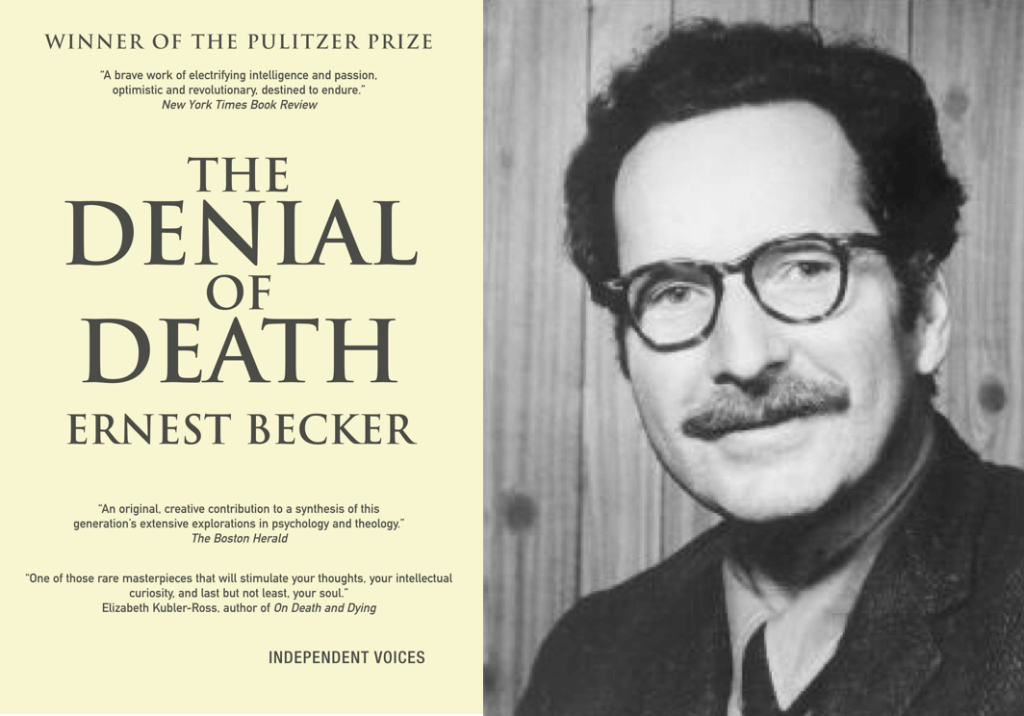

In his <Pulitzer-winning treatise on The Denial of Death (1984), Ernest Becker> argued that the human psyche, regardless of place of birth or skin colour, operates with a deep rooted impulse to deny mortality. Each of us arrives at a world where institutionalized religions and hero-mythologies offer us ready-made and passed-through-the-generations means to deal with our anguish and fear concerning death.

And yet this denialism of demise, this refusal of finitude, which explains the power of faiths despite their incredible claims, is far from immutable. Certainly the denial of death has its historical-cultural mutations and changes also in correlation to society’s level of technological development.

Several sci-fi films have recently dealt with promises of a <technological-fix> for the often unnaceptable facts of death: Elysium’s high-tech 3D-printers of artificial organs and programs of cell-replacement; What Happened To Monday’s project of massive cryogenics leading to a freeze-up of thousands of human organisms destined to a later-on re-animation; or the series <Better Than Us> depiction of challenging surgery being done by highly intelligent and precise robots.

It’s also becoming undeniable that speculative fiction with anticipatory intentions is increasingly dealing with the promise of a post-organic human, with a fusion of brain and computer that would leads us into the brave new world of becoming post-human, carbon-plus-silicon cyborgs, no longer jailed in the usual confines of traditional death. Paula Sibilia wrote marvelously about it in her book (O Homem Pós-Orgânico, not translated into English yet) and the film <Restore Point>, a brand new Czech sci-fi blockbuster, needs to be placed within this context to be fully appreciated.

BACKED-UP FOR RESSURECTION

With its current meaning, the concept of “back-up” – copying and saving data in memory devices – has entered our lexicon very recently, after the technological revolution of digitalization, and it has seen a significant upsurge in its use in recent decades. In its analog incarnation, the expression “back-up” is usually used in a context of military or police operations: when soldiers or police officers are dealing with a challenging task or dangerous mission, they usually call the authorities in charge and ask for a back-up, which means an extra assistance or reforced personnel.

But the term has shifted with computation’s widespread use through all sectors of social life, and now it refers to a process of saving data deemed to be relevant or precious in an extra device (or several). The “back-up” craze is a manifestation of the ever rising technical reproducibility of images, sounds and texts that have reached a level undreamt by Walter Benjamin’s now canonical essay – which needs, of course, actualization for our new predicament.

Digitalization implies that making copies is easier than ever – the process of technical reproduction has been “democratized” and most of us are quite familiar with daily use of commands such as CTRL+C plus CTRL+V (it could be argued that this phenomenon aids in the decay of the aura). In Benjamin’s historical period, technical reproduction of photographs or film negatives was a much more costly and limited phenomenon – you needed wealthy individuals or corporations in the entertainment industry to provide high amounts of capital investments to make copies of films.

Nowadays, the common citizen has the power of technical reproduction with a few clicks or keyboard commands. For example: if I wish my photos and videos taken in Amsterdam to be safe from the menace of unrecoverable deletion, I shouldn’t keep them only in my PC’s hard drive – I should back it up on an extra hard disk and also save it on a “cloud”. Of course this also implies an intricate problematic in political-economy: which corporations are able to provide this backing-up services by selling hard disks or cloud-space (which also need a material infrastructure in data servers), and how should they be regulated by the national state and international law, in order to protect privacy while still allowing for cyber-crimes to be discovered and prosecuted.

We live in an historical period where almost no one judges to be absurd or preposterous to call our world a sphere under unprecedented domination by “Big Tech” and “Big Data” – and that context propels, let’s say, big back-up schemes and big data servers. Several scholars and researchers have delved into this new zeitgeist and have come up with a wide array of relevant critiques (E. Morozov, J. Bridle, J. Crary). This is the context in which to comprehend the brand new strands of cyberpunk sci-fi engaged in anticipatory narratives, a subgenre in which films such as <Upgrade (Whanell, 2018)> and a series such as Upload have explored.

The fact is that the “back-up” mindset – you shouldn’t keep all your cyber-treasures in just one digital-vault – has now mutated into one of the greatest assets for sci-fi creativity. Riding this wave, Restore Point (2023), the debut feature film by Robert Holz, screened at Imagine Fantastic Film Festival in Amsterdam, arrives with a very potent mix of murder mystery thriller and speculative fiction – proposing a technological fix to cheat death. This techno-solution tastes like a mixture of sweet and sour, utopia and dystopia, that makes the viewer, during the screening, oscilate between fear and hope, promise and threat, amazement and fright.

“Have you done your back-up today?” Citizens in the Czech-Republic’s capital are reminded, in huge electronic outdoors and on their omnipresent screens, that they shouldn’t forget to back-up their recent lived experiences. If you happen to die, you will only get a second life, through the so-called restoration process, if you have backed-up in the last 48 hours.

We are in Prague, 2041, and the territory of Central Europe is now fully embarked on the widespread use of a technology that seems to cheat death and also provide profits for new technocrats. Which is always a very problematic, troublesome endeavor: selling salvation can become a bloody mess. After religion, this human-invention that for millenia we’ve used to try and pretend that death will be vanquished, now science promises us that death shall be conquered by an array of techo-fixes: corpses brought back to life in high-tech tanks, brains re-animated and re-activated with backed-up data etc…

A co-production between Czech-Republic, Slovakia, Poland and Serbia, Restore Point deals mainly with the activities of an Institute that has mastered the restoration process but is also undergoing a privatization process that is highly controversial. Its CEO, Rohan, talks about the marvels of the private sector grabbing this market, but some journalists present at the press conference are not easily convinced: wouldn’t this mean that only a wealthy elite would be able to purchase the restoration process? While a majority of citizens gets locked out of this V.I.P. area, condemned to that old death we had accustomed to see as an unchanging factor of the human condition?

The plot thickens with another explosive ingredient: there’s an organization called “River of Life” that authorities describe as terrorists who are jeopardizing the whole project of the Institute of Restoration. The film deals with widespread social anxieties concerning terrorist attacks and the story begins with newsreels about a bus bombed by River of Life militants and that has killed several people. Thanks to the outstanding miracles of science, however, the corpses of the victims could be restored and brought back to life.

The film’s protagonist Emma Trochinowska (played by actress <Andrea Mohylová>) is a police woman and she has very emotional motivation to be engaged in a war against the River of Life terrorists: she was married with Peter, a pianist, who was supposedly killed in a concert hall in Dresden after the terrorists took over the precinct and began killing hostages one-per-hour.

Peter, unfortunately, was killed last, when more than 48-hours had elapsed since his last back-up, which means the Institute of Restoration couldn’t violate its rules and bring him back to life. Peter is dead for real – and Emma is now left with the souvenirs of her deceased husband not in the form of old-style photographs but rather in the guise of 3D projections – his “ghost” from the past, a 3D recorded version of him, can be summoned to be her piano teacher.

Emma’s main job in the film is to solve a murder case – one of the scientists who developed restoration biotechnology, David Kurlstat, and his wife Kristina, have been murdered in mysterious circumstances. Restore Point leads us to a whodunit plot far beyond what Agatha Christie and Conan Doyle dreamt of. It also shows that Kenneth Brannagh’s recent incursions in classy, well-made and compelling tales of Hercule Poirot’s investigations, straight out of Agatha Christie’s books, in his <trilogy Murder in The Orient Express, Death on the Nile and A Haunting In Venice>, fails to explore the ways in which current technology transforms radically the murder mystery genre.

The detective of nowadays explores the oceans of big data, scans photographs in search of tiny pixels, works helped not by a flesh-and-bone ally, such as Watson was for Sherlock, but rather with the help of A.I. and search engines of huge databases. In Restore Point’s complex plot, Emma suspects that a certain Viktor Toffer is involved in this crime and sets up on an action-filled chase to arrest him. But Toffer is far from being a one-dimensional villain.

The film deals a bit with the matters of hacking and cyber terrorism because the Restoration Institute is currently undergoing a crisis due to a virus, which Toffer is suspect of having inserted into the system, that deletes the back-ups. It’s a plot that might make viewers recall Fight Club’s Space Monkeys plot to erase credit-card inequalities through terrorist bombing plus cyberattacks. It also shares a lot of themes with that awesome series Mr. Robot, still under-rated and deserving of more scholarly analysis.

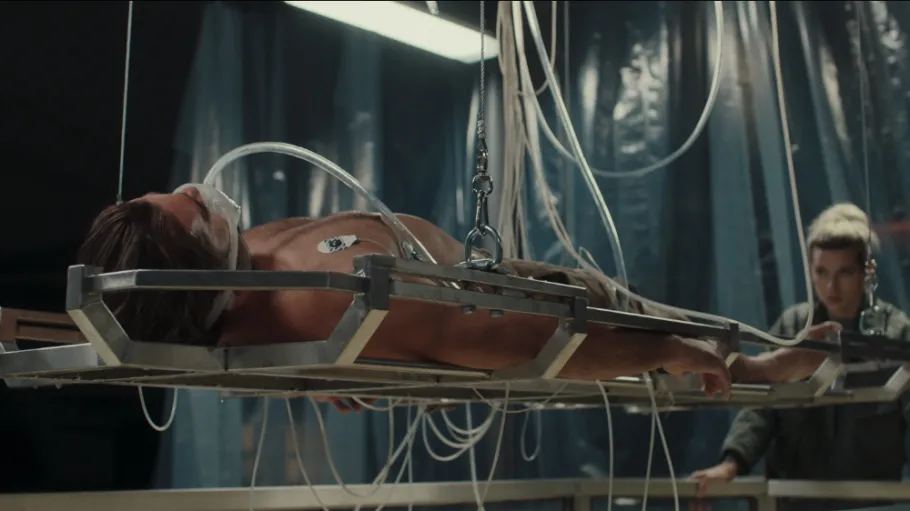

The strangest aspect of the plot is the relationship developed between the police woman Emma and the restored version of David Kurlstat, murder victim brought back to life from an old-backup, in stark violation of the 48-hour-rule. Emma gets to experience, through David’s restoration, the side effects of the process kicking in his body. David is sick, coughing a lot, and needing constant injections on his bloodstream. David also reveals to her that the human body when “restored” is far from being pleasant to inhabit and is also prone to accelerated aging processes. She also discovers that some people are privileged enough inside this restoration biz to be brought back to life with a “gift”, a talent they didn’t possess in their normal lives – David, for instance, discovers he can play Debussy at the piano quite fluently in his recovered body.

SPOILER ALERT

The most mind-boggling aspect of the plot’s grand finale deals with the notion of River of Life being not a real terrorist organization willing to destroy the Restoration Institute – it’s suggested that CEO Rohan created it and financed all of these bombings and attacks. To create panic in society and make restoration purchases upsurge, it’s a good marketing plan to make the common middle class and upper class folks be immersed in horrorism (Cf. Cavarero). The film deals with the insurance market in a context of widespread “unnatural deaths”. This is anticipatory narrative for the coming age of biopolitics.

David is also far from being a good, generous scientist; he’s revealed to be actually a jealous husband, infuriated by the affair that Katarina is having with Toffer – which isn’t about sex only, but also about worldviews conflicting – Katarina has moved away from David’s mindset and seems to have become an ally of the rebels.

Toffer seems to be an almost archetypal figure for anarcho-primitivism – and also the commune of his aunt hints at that. I’m using this label of anarcho-primitivism inspired by the writings of John Zerzan to refer to people who believe the hi-tech restoration system to be deeply flawed from the ethics and politics viewpoint, and ripe for radical critique and practical destruction. The commune’s inhabitants live with no Internet or digitalized telecommunications; it sets itself apart from Prague’s tech-frenzied metropolis; it knows there’s something rotten in the Czech’s technocracy.

The film reaches its finale with a sort of happy end – the violent death of our protagonist Emma, played by an actress with a blonde beauty reminiscent of Scarlett Johannson; Emma is killed by the Europol cop which acts as a puppet for Rohan’s Institute. But the bitter death of the beautiful protagonist would send the spectators out of the screening and back into the world with a bitter taste in their tongues. No, the death of a female heroine is not a good choice for a film that needs money coming in from the box office to pay for its costly production. Emma, of course, gets restored.

She comes back upgraded. She now has the skills at piano-playing that made her deceased-husband Peter a well-renowned orchestra musician. The film ends in an almost optimistic key, marveling at this back-from-the-dead beautiful blondie that plays Debussy with dexterity. It’s a satisfying finale, but it softens the shocking ideas the film communicates.

I would have ended this a little bit differently – with a quick injection of Cronenberguian body horror. For any viewer not suffering from amnesia, the memory of side effects on David’s restored body lingers on the mind and leads us to think this: by the time the film ends, Emma is on an imminent road to feel those terrible symptoms also.

Perhaps it’s almost heresy for a film critic to abandon analysis of the artwork as it is and to propose that the director and screenwriter should have chosen otherwise. But I’ll try my luck with this sort of contrafactual criticism and go on to say: I would have ended this film in dissonance. She would be playing the piano beautifully, showering us with awesome melodies, and then – all of a sudden – her body would fail and falter. Debussy’s music would be shattered by discord, and the happy end would be buried under the rubble of dissonant keys and a cluster of noise.

This would be, perhaps, an impopular closing scene, but I can’t help but feel dissatisfaction when filmmakers deem necessary to end a very dystopian oeuvre in a “hopeful” key. Hope sells, I know, but this sort of closure seems a bit like commercialism, like submission to the entertainment industries pressures for happy endings. It seems to close doors for further discussions because it sends the spectators home with the impression that things turned out really well after all. When an alternative closure, such as the one I’ve imagined and depicted here, would be better to haunt us out of the movie theather and impel us to engage in fruitful discussion.

Another criticism I would like to make concerns the fact that the film’s script refuses to explain in detail how the practical science of restoration really works. It asks us to suspend our disbelief and only shows us briefly how the deceased bodies are brought back to life in tanks. Well, this seems to me a refusal of the film to engage more deeply with how this possibility of hybridization of brain and computer would actually be accomplished; the murder mystery and the action scenes get front row, and speculative science – which is at the core of the greatest science fiction – lags behind.

Despite that, this film is an excellent addition to the Czech sci-fi canon and puts Holz in our list of filmmakers who should be watched in his next steps – it’s a debut feature which manifests a very promising sci-fi director in his first emergence. It also proves that Karel Capek’s nation is still capable of providing us with mind-blowing and thought-provoking works of art in the futurology field: in the 1960s, some of the greats sci-fi films came from the Czech territory – such as<Ikarie XB1, by Pólak, based upon the S. Lem novel>, one of the greatest space-travel films and an inspiration for Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

There’s no end in sight for fictionalized accounts of the saga of an animal that refuses to be mortal and insists on attempts at cheating death through an ever-growing array of man-made artificialities. And yet death, even tough changing its manifestations, is still an unvanquished and un-deletable part of our condition. No matter how technology changes and advances, we’re the always impermanently alive beings which struggle, in fact and fiction, to overcome what is perhaps the insurmountable mountain.

Eduardo Carli de Moraes

Amsterdam, October 31st 2023

Seen at the Imagine – Fantastic Film Festival

Read also: Czechoslovak science-fiction films – Variety Review

Publicado em: 01/11/23

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes