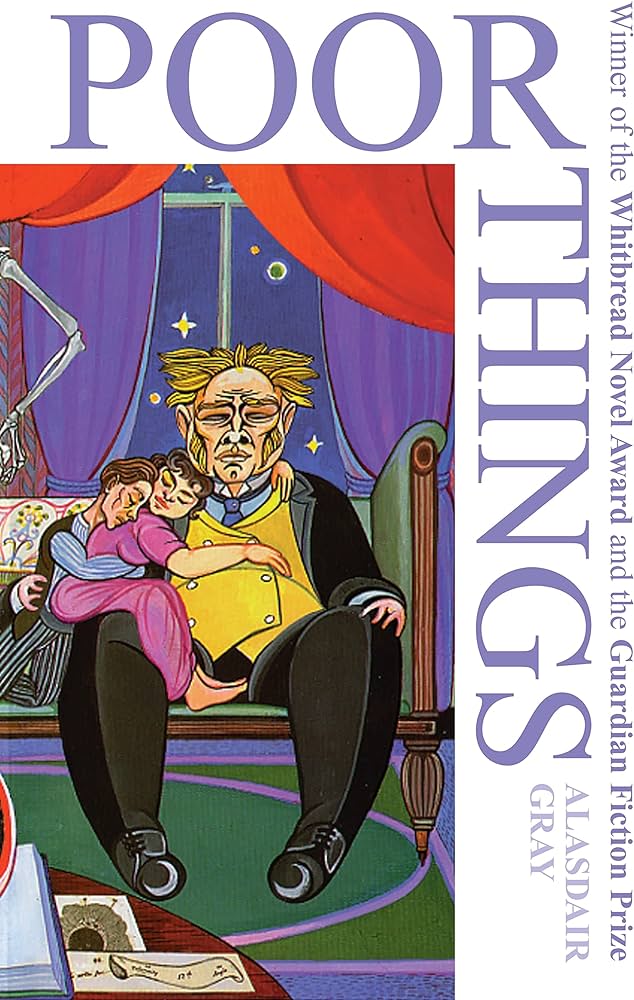

POOR THINGS: Lanthimos freaky-tale reloads Frankensteinesque storytelling in a masterpiece of the Greek Weird Wave

<POOR THINGS> (2024), this terrific cinematic triumph by Yorgos Lanthimos, is a freaky-tale (with no fairies involved!) that belongs to the Frankenstein-lineage. It’s brilliantly outrageous, profoundly impolite and would perhaps be one of the best films ever made according to the Greek philosopher <Diogenes of Sinope> (who lived between the years 412 and 323 before Christ) – if he was alive and had been converted into a 21st century cinephile.

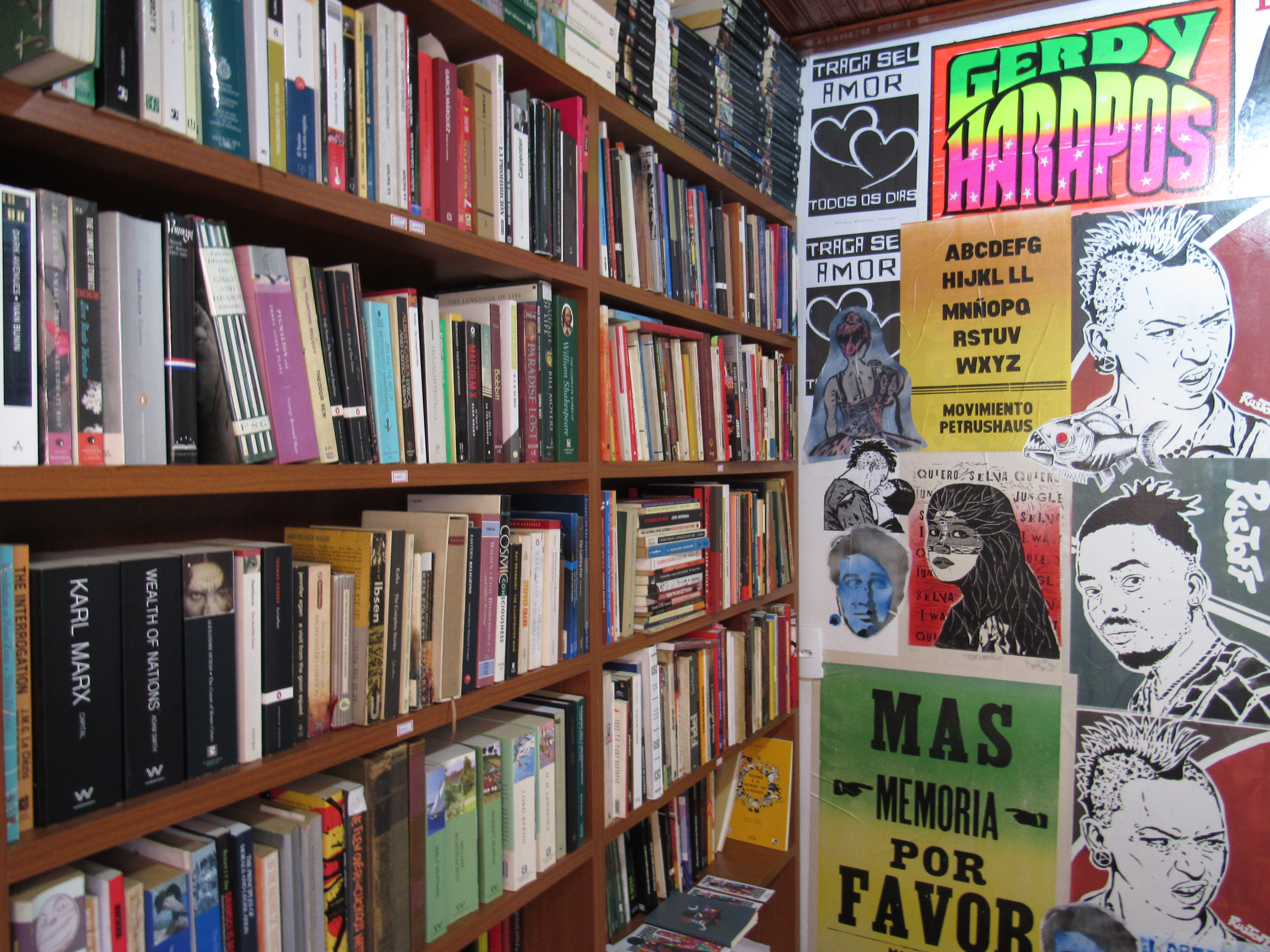

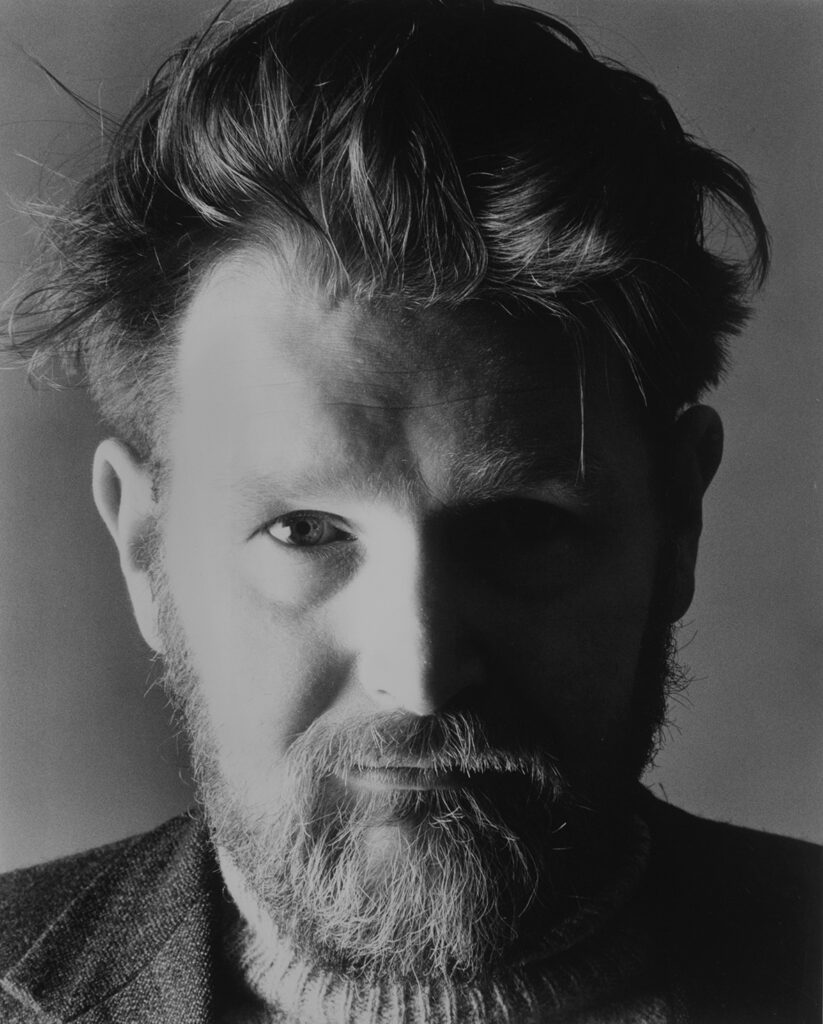

Based upon a novel by the <Scotish writer and visual artist Alasdair Gray>, published in 1992, the film proves that the seventh art is at no danger of dying by cliché asfixiation. At least so long as Lanthimos is around, tuned to the fictional creativity of figures such as A. Gray and M. Shelley, and using his cinematic brilliance to spearhead the production of artworks so awesome as Poor Things, a theatrical magnum opus of queer cyborg transhumanist feminism.

Fearlessly affronting solidified social norms, sexual tabbos and dogmatized preconceptions, Lanthimos on top of it brings us to the funniest of his films. He manages to apply some surgery that removes from mainstream film production the commonplace, or the reproduced-to-exaustion, and injects into filmic culture a good dose of weird, of queer, of steampunk, of cyborg feminism. It’s not a small nor neasy feat. It’s prodigious.

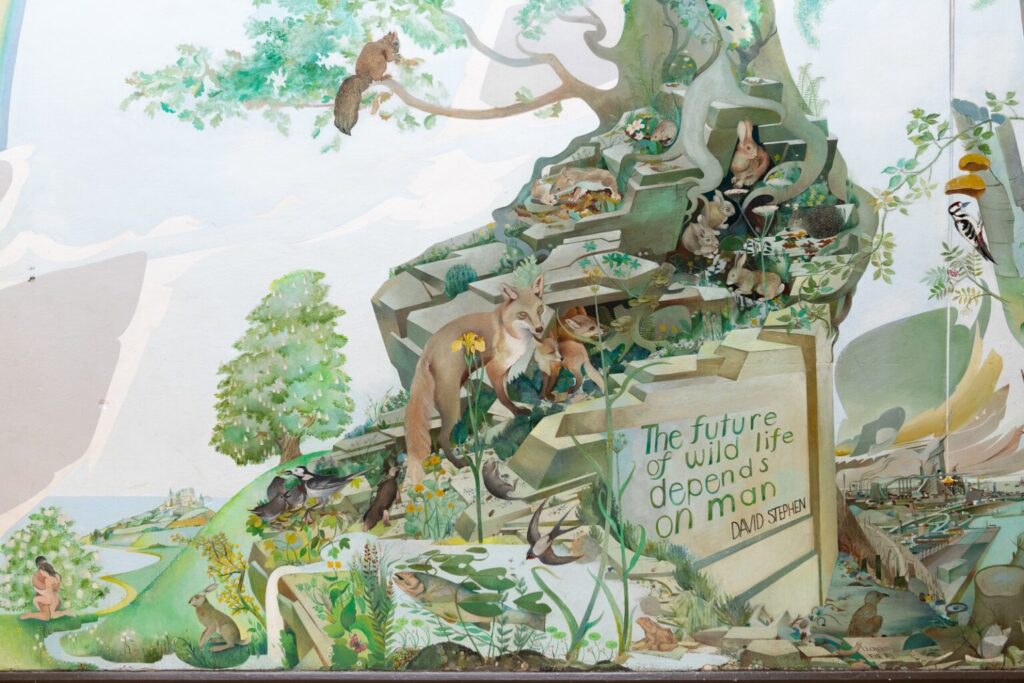

In order to suture up new points of view, opening up ways for the cinema-to-come, I feel Lanthimos made an excellent move to approach the multi-language work by Alasdair Gray – which was also a painter, muralist and illustrator of his own writings, in a manner that evokes William Blake and is shown at its peak in the ambitious illustrated novel Lanark (1981).

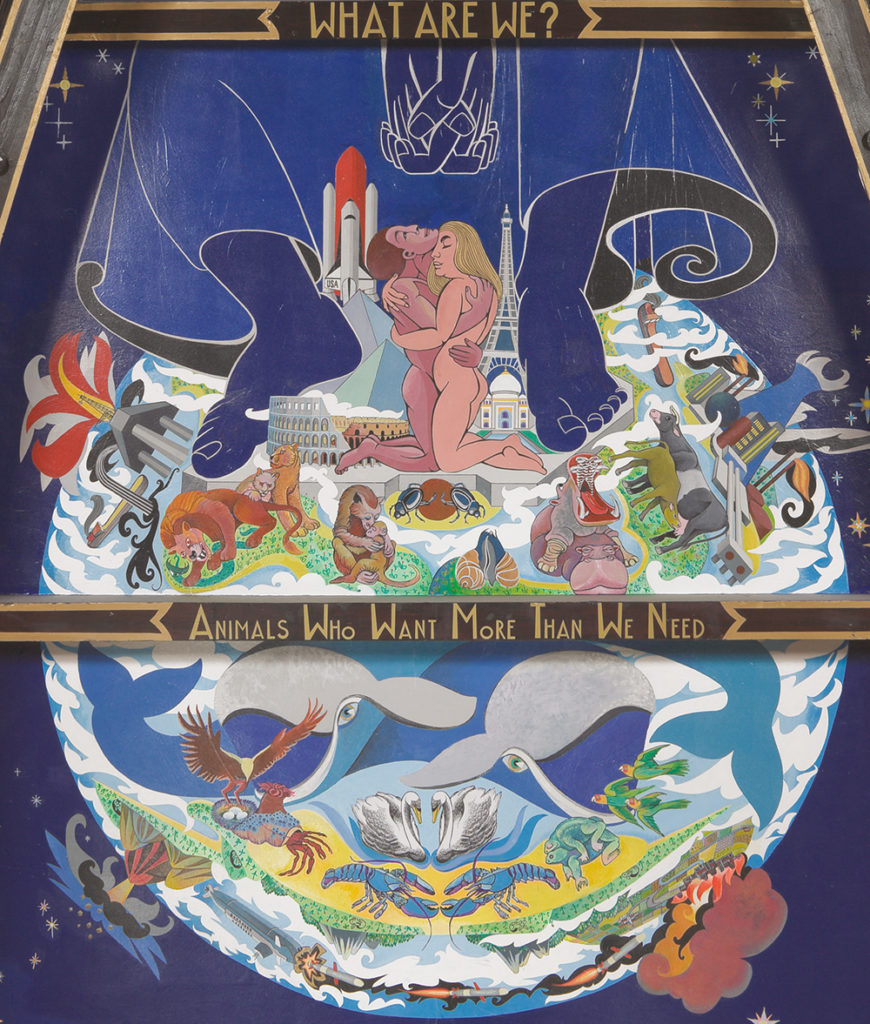

Above: an artwork by Alasdair Gray in <Òran Mór, a cultural venue in Glasgow/Scotland>, and three book covers for different editions of his novel “Lanark” <ACESS/DOWNLOAD EBOOK>.

Born, raised and deceased in Glasgow, Gray – who died in 2019 – seems to be now gaining momentuum to become posthumously recognized as one of the greatest artists from the U.K. for the last decades.

In this article, I’ll argue that the most fruitful path to decipher this masterful work has to follow the lead of an hybridization process in which the mixture or mélange between the creativities of Alasdair Gray and Mary Shelley play an eminent role. But also this film’s embedded philosophy won’t be grasped without a deep understanding of classic greek cynicism and its leading figure, Diogenes. I also argue, last but not least, that this film infuses our culture with a welcomed dose of whacky queer feminism and feels quite favourable to the emergence of post-humanism.

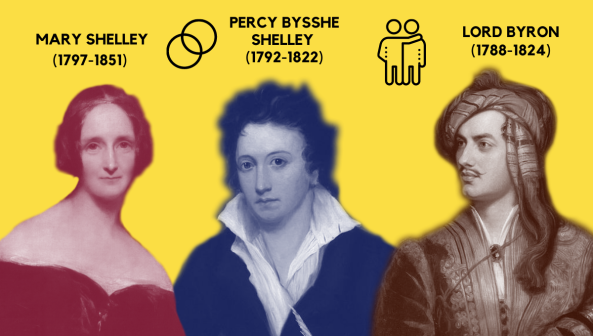

2. TWO TRIANGULATIONS: Mary, Percy and Byron; Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin and Baby Mary

She was 19 years old and ready to write an immortal tale. She was under the impact of the deadliest volcanic eruption ever, and she had lost her mother when she was a baby of 10 days, even tough she would througout her life proudly follow in the footsteps of Wollstonecraft, her mommy and one of the greatest intellects that ever lived.

In a novel now widely regarded as a masterpiece of universal literature and probably the first chef d’ouevre in the science fiction pantheon, the young author Mary Shelley made it explicit in her subtitle: Frankenstein was a Modern Prometheus. A revival of an ancient greek myth about a titan who stole fire from Olympus and was severely tortured as punishment by a wrathful Zeus.

There’s a 19th century remembrancing or contextual framing that’s important to recall here for a deepened appreciation of Poor Things and its many marvels. I’ll do that by referring to two human triangles: the first triangle is composed of Mary, Percy and Byron, which famously had a bet in Pisa to see which of them would write the most horrific horror tale (the trio is also represented in James Whale’s The Bride of Frankenstein, 1935).

The second triangle is composed of Mary Shelley, her mother Mary Wollstonecraft and her father William Godwin: in another very well-known biographical tragedy, the brilliant essayist and writer Wollstonecraft died a few days after giving birth to her daughter Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin. Orphaned since early childhood, Mary the daughter would be raised by her distinguished father, William Godwin, and would later marry the poet Percy Shelley and change her name to the now solid gold nom de plume with which she now stands in literary history – Mary Shelley (her life was also made to fit into a fairly good biopic).

From the first triangle, this highlight: Mary’s tale, Frankenstein, was such an astonishing artistic triumph, with wide repercussions in posterity, that it overshadowed both Percy’s and Byron’s attempts at horrofic storytelling at that occasion in Pisa. There’s no doubt about it: Mary won that literary contest and her horror tale made it into the history of creative writing – a young woman, fighting against two males, knocks them out and proves triumphantly to be the most brilliant amongst the three in quickly crafting a harrowing tale. Poor Things will explore a similar track: Bella Baxter will triumph over the damned patriarchs that wish to chain her and confine her.

From the second triangle, this highlight: Mary, the daughter, could not have an actual carnal relationship with the living body of her mother Mary Wollstonecraft; as a kid, the woman we know as Mary Shelley was an orphan, the famous daughter of the deceased genius philosopher and activist who had written The Vindication of Women’s Rights. But it’s also beyond any reasonable doubt that the writings, the thought, the life events of Wollstonecraft truly nurtured Mary the daughter through the mediation of her father. I’m perplexed that most critics of Poor Things seem totally oblivious to these 2 human triangles here evoked.

It’s also worthwhile to highlight that the myth of Prometheus, brought to Modernity, doesn’t apply to the “monster” but to its creator, Dr. Victor Frankenstein – it’s in him we should see the titanic figure, with its obvious equivalent in Godwin Baxter. The creatures – the one Victor creates and we erroneously name Frankenstein (which is the surname of the mad scientist type that creates him), and Bella Baxter – are there to show the out-of-controlness of some scientific experiments. The invasion of chaos where one should expect some laboratorial order.

Dr. Victor Frankenstein and Godwin Baxter are also demonic figures, titans of heresy, because they become rivals of the official god, the established deity. Their creations are not “godly”, thus the temptation of calling those critters sons and daughters of the devil. We won’t fall into the trap of that temptation – here, in this work of art, there are no easy lines drawn between the sons and daughters of the devil, absolutely evil, and the creatures of the right god, thus absolutely good – let’s have the courage to toss aside that childish manicheism and venture into the realm of complex hybrids and profound ethical ambivalente.

One of Poor Things many virtues is that it never debases itself into a moralistic, manicheistic piece. It goes way beyond traditional good and evil – into the weirdo ethics and cyborg ontology realms that add up to make this a highly original A.U.F.O (an audiovisual unidentified flying object).

3. OUT OF OUR PERIMETER

Experimentation, etymologically, means going out of the perimeter. Bella Baxter (Emma Stone) is described as “an experiment” by her creator, the equivalent of Dr. Victor Frankenstein, called (in a wink of an eye to Mary Shelley’s father and Wollstonecraft’s husband) Godwin (the character played by Willem Dafoe). The film doesn’t repeat a formula concerning Frankensteinianism; it builds something with new flavours inside the lineage in which it belongs. Lanthimos is also into the field of Cronenbergian body horror, it connects with an undercurrent in the history of cinema inaugurated by Tod Browning‘s Freaks (1932) and followed by David Lynch‘s and Jodorowsky‘s freaky filmographies, and also has a taste of that unrealistic satire in the vein of Wes Anderson or Todd Solondz.

Riding the crest of a cultural wave that has been nicknamed GREEK WEIRD WAVE – it’s actually the name of a <4-film retrospective currently running in Amsterdam’s LAB111 which includes screening of The Lobster, The Favourite and Killing of a Sacred Deer>, Lanthimos films make us wonder about the destinies of words such as nigger, queer, weird, punk etc. They were once negative, used to offend, a weapon on the mouths of bullies; but the people who got thrown at them these demeaning terms, the ones who were targets of these hurtful words, then started using ‘em in a more positive sense, as something to be proud of. The “black power” movements are all about empowred niggers; in LGBTQ+ circles to be queer becomes hip and cool, instead of “straight”, which gets in gay and lesbian circles the meaning of narrow, confined to binaries and rigidly conventional. Poor Things is a film that sets in motion furthermore a “good weird” tendency; our protagonist is weird, indeed; she’s described as a “retard” at the beggining of the tale, but her evolution or development is astonishing.

This evokes in me another interesting framing or contextualization: it’s a work of art about the changeness of life, our hability to upgrade or degrad. Bella is, on screen, such a colourful and interesting character because she’s ever changing, chasing new experiences, getting enraged with anyone who tries to confine her. The caricature of male toxicity is played by Duncan (Mark Ruffalo) – when he kidnaps her and gets her on the boat, treating her as his private property (he orders her to enter into a trunk etc.), the film gets philosophical. A debate about cynicism is brought upfront. Bella meets a young cynic, a black philosopher who seems to think humans are essentially cruel beasts and that “politeness” is just a veil hiding that.

This man acts upon her as some sort of demonic enlightner: in the film’s most heart-wrenching scene, he takes her to see “what the world is really like” – and then she witnesses lots of dead babies and kids in Alexandra’s neighborhoods where the poorest inhabitants dwell. She’s traumatized by this, she’s thrown into a trance of charity and pity – she becomes similar to a Frankensteinion version of Rousseau‘s noble Savage.

But, more explicitly, she’s connected with *Diogenes of Sinope* in the wonderful scene where she’s reading Ralph Waldo Emerson in the deck of the boat, and the furious toxic male interrupts her because he wants sexud services; she tells him “get out of the way of the Sun” in a wink-of-the eye to the famous episode of Diogenes and Alexander the Great. See below 2 recent photos I took inside the Louvre Museum in Paris that depict that famous, antological scene:

I’m also perplexed of how critics of this film set this element completely aside and don’t seem to take notice that Poor Things, besides belonging to the Frankenstein tradition, also connects to and produces a revival of classic philosophical cynicism. It has been brought to the crest of a wave in mid 1980s by the late Michel Foucault course at Collège de France about paressia, or the courage to speak the truth. And nowadays seems to be resurfacing and going way beyong the traditional misconception that connects cynicism with hypocrisy and fakeness – when it’s quite the opposite.

The cynic, in a classic sense, feels authenticity to be a greater value than politeness; and the laws of nature – physis – to be the real powers that lord over us, and not the laws of convention, always frail and relative – the smashable nomos. In one of the greatest lines in the film, the Black Diogenes philosophises: “Hope is smashable, realism isn’t.” Poor Things, instead of idealistic naiveté or puritanical dogmatics, invites us to merrily join the queer parade of realistic cynics daring to speak thuth to power.

Bella Baxter is un-conventional, weird, unruly and pretty reckless (would she be a good leader for an emocore band made of cyborgs and queers?), and the reason for that is the childish brain that has been inserted into her full-grown woman body. Her sexuality in a state of explosion and exploration takes her far away from ascetic ideals or Victorian pruddishness. In <a recent interview conceded to Little White Lies, Yorgos Lanthimos talked about how cinema can confront taboos about sex (click to read – opens in new tab)>.

Poor Things is about a technological experiment that has always been taboo in the actual scientific community: a brain transplant where you take the agonizing body of pregnant woman who has just attempted suicide, and then take the baby out of her almost lifeless organism, and then substitute the brain of the grown women for the baby’s brain, then proceeding to produce, throgh electricty worthy of lighting strikes, for the purpose of reanimation.

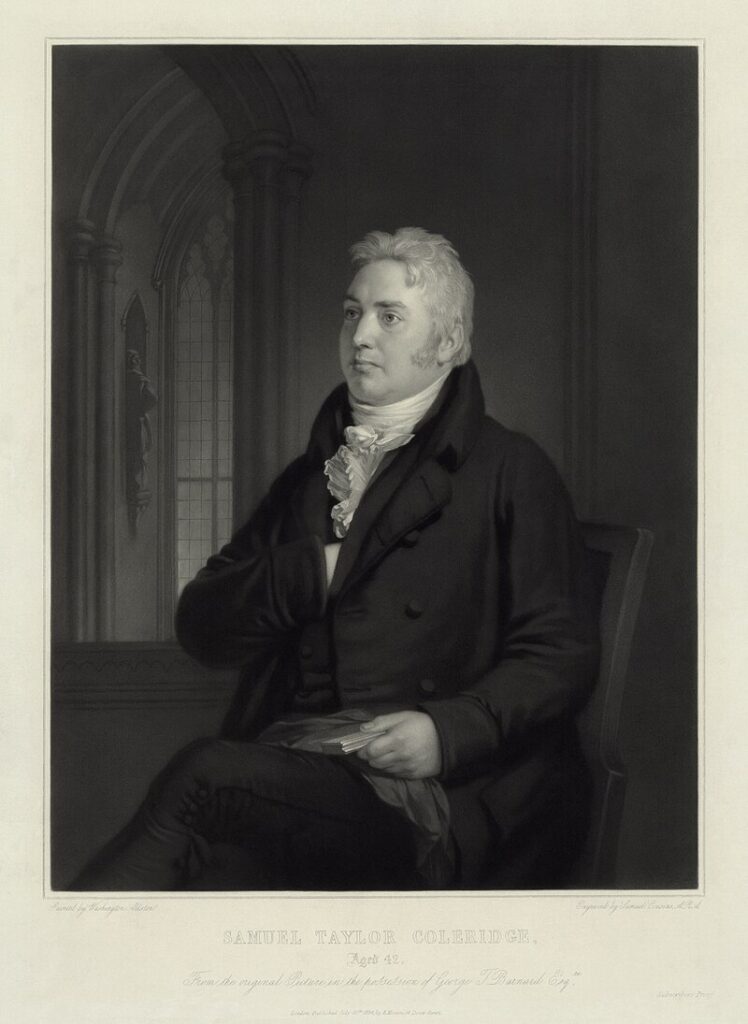

4. DEAR AUDIENCE: PLEASE EMPLOY SOME POETIC FAITH

Of course this is phantasy-science and Lanthimos doesn’t waste any time trying to convince us of the plausibility or feasability of the experiment. It asks of us the famous Coleridgean “willing suspension of disbelief” or “poetic faith”.

It’s quite obvious that this film is very far away from any realistic aesthetics: the cities of Lisbon, London, Alexandria and Paris aren’t actually filmed as they are (or as a neo-realist flick would depict them), or as a documentary would show them; they appear in front of our eyes transfigured by some procedures I’d call Tim Burton-esque linked with lots of steampunk visuals and fish-eye lenses.

The film also bears resemblances to Ruben Ostlund‘s films: Lanthimos is also a provocateur willing to target the wealthy and powerful, and I couldn’t help but remember The Triangle of Sadness while I watched the Poor Things boat-scenes.

Before being turned into Bella, she was a wealthy wife locked in a golden cage, a woman belonging to the aristocracy and pushed into suicide by jumping off a bridge by one hell-of-a-husband, a cruel military man, the embodiment of the wealthy class’ cruelty against servants.

The most interesting aspect of this freaky-tale for an ethics debate lies in how Bella goes from monster to prodigy; she’s a fast learner and quickly becomes a witty feminist, one of those empowered, head held high, “my body my rules” kind of chick. She gathers experience and money by whoring in Paris and finds out about several kinds of male neurosis – aggressiveness, jealousy, proprietorship – in the men around her. After all, hen daddy, the mad scientist, deeply scarred in his face, becomes the most morally ambiguous figure in the film.

Bella actually treats him as a god, her creator, and she ends up being very sympathetic to the dying man’s agony. If, in the “teenage” phase of her emotional and cognitive development, she has rebelled against this paternal authority, raging against the bars that tried to confine her, at the end of her journey, more mature, she feels a sense of duty and gratitude towards the dying equivalent of Dr. Victor Frankenstein – here, Lanthimos’ film part ways with Mary Shelley’s much more pessimistic approach to the contradiction between creator and creature.

This film could be described as aesthetic provocation without a grain of moraline (as Nietzsche called the substance that moralists, zealots, preachers and demagogues of several isms try to instill upon us); it’s perhaps absurd to try extracting the “moral” of the freaky tale with no fairies when we leave the projection room. But I think it’s possible to state that cruelty and evil conduct are here embodied my “normal male humans” and those who seem at first sight to be monstruous and repulsive turn out to be weird heroes of the Lanthimos pantheon.

5. THE NEW WILD WILL BE WEIRD: TOWARDS HYBRIDIZATION AND POST-HUMANISM

The film also contains a whole bestiary of chimeras and hints of biologic chaotization through inter species surgery and genetic engeneering. We’re thrown into a world filled with hybrids, a theme very cleverly explored in the writings of the french philosopher of science Thierry Hocquet, who deems hybridization – and of course cyborgs are also hybrids between the organic and the machinical – an excellent way to escape traditional confining dualisms. Poor Things is not pessimistic, misanthropic or nihilistic; Bella Baxter is actually trying to prove that the Black Diogenes was wrong in assuming cruelty is the essence of the human.

Even tough the film closes the doors to any naiveté and utopianism that would portray as desireable the figure of the pure organic being – instead it enjoys its bestiary of hybrids – and yet leaves open doors to laughter through phantastic sci-fi good-weird satire. Bella Baxter ends up acting out in revenge against the evil husband that led her previous self to suicide by imposing a degradation or de-evolution. It’s the happiest ending Lanthimos ever filmed and yet it’s drenched in vindictive cruelty.

With no naiveté, this is a cinéaste de la cruauté, an Artaudian enfant terrible, that ends up with a happy end in very cynical style – Bella aimed to deny the cruelty-thesis, and look how joyful she seems, at the end of the road, when she takes revenge on the guy, degraded into a retarded, grass-eating, deprived of human lógos, man-goat.

Lanthimos, as a cultural agent, seems to be the main figure responsible for flipping the coin of weird from negative to positive, or from repulsion to attraction. This weird protagonist, so marvelously played by Emma Stone, invites us to join forces with an emergent whacky and politically incorrect queer feminism. While watching it in Cinecenter, Amsterdam, in a very crowded session, I could feel the power of attraction it has over audiences, both the laughter and the horror it provokes, even tough it’s far from the usual blockbuster and massive ticket seller. This film can be disturbing, annoying, confusing and unbelievable (for those incapable of poetic faith, who crave for realism, it may seem like a filmed acid trip with not much grains of reasoning in its structure).

By some hard to decipher connection of ideas during the screening I often remembered of “Flowers for Algernon”, a novel by Daniel Keyes which inspired <a masterful film, “The Two Worlds of Charlie Gordon”>. Both protagonists start off as retards and make their way into almost geniality. Both are tales of cognitive acceleration and faster-than-usual learning. And both highlight also the fact that in life’s pendulum we shouldn’t ever believe in the possibility of true stability. Expect change cause is change of the cosmos’ essence.

Another point to deliberate upon concerns humour. I found this a very funny film – which means it was in harmony and sync with my own sense of humour. I also think Diogenes is the funniest of philosophers -a performer of gags, tricks and practical jokes. Bella is Diogenesque, it makes us wonder why cynicism is so outrageously humorous. Breaking with the norms and dogmas of “polite society” can provoke much laughter – including on normopaths.

Poor Things seems a joyful manifesto to the widespreading Post-Humanist Age. I write this inspired by the scribblings of Rosi Braidotti and Donna Haraway, two of the world’s leading philosophers. The human as we knew it is dead and gone – but perhaps not yet buried enough. Poor Things, an expression of pity (when you see children in the slums, going hungry, shivering in the winter’s cold, you might cried out “poor things!”), ends up pitying not the female-Frankenstein critter, she’s turned into a weird heroine, shee comes up on top.

What is dethroned and thrown off its pedestal is the normal predator, the usual oppressor, the milleniums old dominion of patriarchs. The queer cyborg, the monstruous experiment, ends up being much better than the previous incarnations of the human – namely, in toxic dicks, control freaks, patriarchal authoritarian assholes, here sent down the evolutionary ladder into the status of degrating figures headed to devolution and de-evolution. It speculates about the avenir, the what’s-to-come, suggesting we’ll evolve into post-human critters, weird hybrids, ever-changing cyborgs, surrounded by creatures no biology book of today describes, queered up to the core of our existential roots.

Eduardo Carli de Moraes

Affiliated researcher at ASCA-UVA, Amsterdam

February 2024

THINKERS AND PHILOSOPHERS MENTIONED AND RECOMMEND FOR FURTHER STUDIES:

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE TO READ:

CAITLIN, Love. Drawing and Imagining. In: The Paris Review, 2017.

VIDEOS IN BRAZILIAN PORTUGUESE:

FURTHER READING:

https://cinegnose.blogspot.com/2024/01/um-manifesto-ciborgue-e-reconfiguracao.html

SOCIAL MEDIA SHARING:

Publicado em: 21/02/24

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes