MANUFACTURED WASTELANDS: A brief history of the Anthropocene

INTRODUÇÃO

O conceito de Antropoceno, longe de consensual, está hoje imerso em controvérsias – entramos mesmo em uma nova época da geohistória e este é o nome mais adequado para batizá-la? Independente de como cada um se posicione quanto à pertinência da nomenclatura, é inegável a proliferação do termo na academia, no mercado editorial, na produção artística em todas as linguagens.

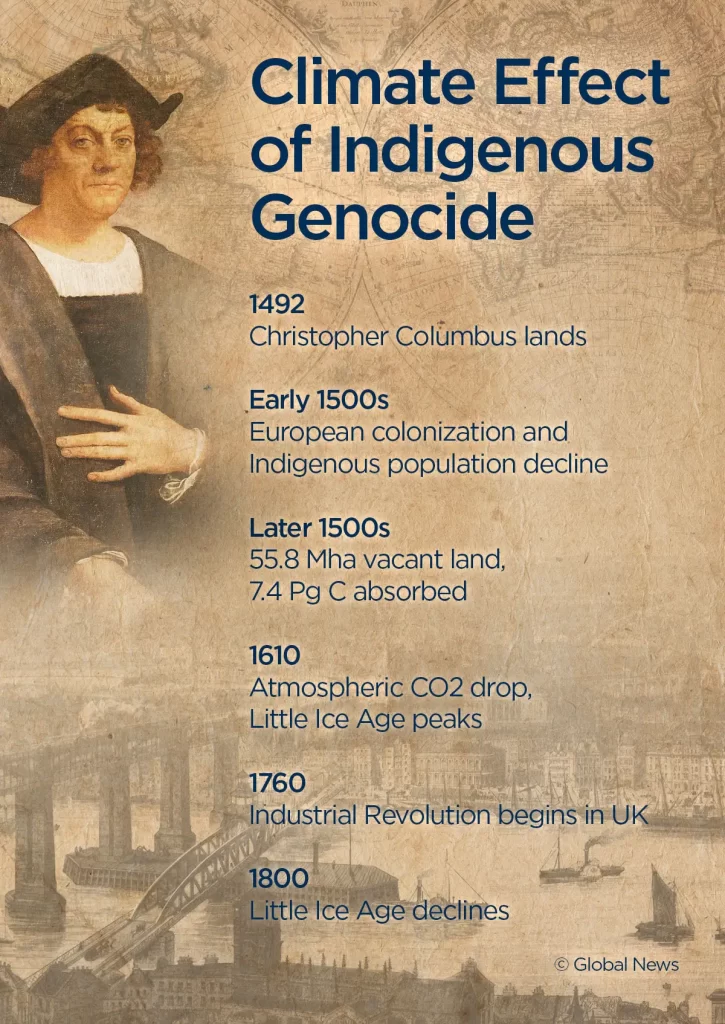

Neste artigo, a partir das obras de Graeber/Wengrow e Earl C. Ellis, e também em interlocução crítica com as teses de Rosi Braidotti e Andreas Malm, analisamos um caso exemplar: a tese da <“Pequena Era Glacial”> (ocorrida a partir do fim do século 16) e que seria a primeira evidência da capacidade de alteração radical do clima planetário por agência humana. Ela teria ocorrido quando mais de 90% da população nativa daquilo que os europeus chamariam de América foram dizimados pela “Conquista” imperialista.

Questionando a ideia de que o Antropoceno começa com a Revolução Industrial, escrevem Graeber e Wengrow em “O Despertar de Tudo”:

“Há quem situe antes a origem do Antropoceno, remontando ao final do século 16 e início do seguinte. Nesse período houve uma queda global na temperatura atmosférica – parte da chamada “pequena era glacial” – que não se explica por forças naturais. Muito provavelmente a expansão européia nas Américas teve um papel nesse ponto com talvez 90% da população indígena aniquilada (de um total estimado em 60 milhões de habitantes). Em consequência da conquista e das doenças infecciosas as florestas retomaram regiões nas quais o cultivo em terraços e a irrigação vinham sendo praticados por séculos. Na Mesoamérica, na Amazônia e nos Andes, cerca de 50 milhões de hectares de terra cultivada podem ter voltado a ser áreas naturais. A absorção de carbono pela vegetação aumentou em escala suficiente para mudar o sistema planetário e desencadear um período de resfriamento global impelido por seres humanos.” (GRAEBER; WENGROW: 2021, Cia das Letras, p. 282-283)

O artigo – em inglês (tradução em breve) – partilha algumas de minhas pesquisas conectadas ao doutorado em curso e em que analiso também as mobilizações sócio-políticas atuais que clamam por re-wild e re-forest (re-selvagização e re-florestamento) como soluções plausíveis para a catástrofe climática cumulativa que estamos começando a encarar (e que só vai piorar) e para a Sexta Extinção da Biodiversidade planetária – que está em acelerado curso enquanto a construção de pipelines e a extração de combustíveis fósseis e a pecuária industrial e o agrobiz agrotóxico prosseguem numa insana escalada de rumos suicidários. – Eduardo Carli para A Casa de Vidro

MANUFACTURED WASTELANDS

It’s a trending topic, a buzz word, a “cognitive commodity” (says Rosi Braidotti): the Anthropocene is gaining ground, but what the heck is it exactly? A valid scientific theory bound to be embraced almost consensually? Or a quick-to-be-demodé hype-concept?

I’m far from satisfied with Andreas Malm response, even tough I share most of his critiques, when he calls it a myth: “blaming all of humanity for climate change lets capitalism off the hook”. The statement is true enough – it’s not humankind as a whole the entity to be blamed for the mess we’re in, and of course capitalism and global warming have causal connections, but does that make the “Anthropocene” into a myth?

Is it really the right word, or is Malm only equating ideology as false consciouness with the term myth, thus ignoring all the complexities – exposed, for instance, by Cassirer’s philosophy of symbolic forms – pertaining to how myths participate in the history of the human condition?

We might dislike the nomenclature (after all, Anthropocene really sounds like a word at least suspect of anthropocentrism;, we might think it’s the wrong word, but are we justified in desqualifying the work of a network of scientists that came up with this proposal, and seeing them all as puppets of capitalism’s cognitive acceleration that proliferates “multiples of one” in the realm of knowledge production (which seems to be Braidotti’s core-critique)?

Really? Crutzen, Stoermer, Seuss, Vernadsky, Lovelock, Margulis, a whole bunch of other researchers, which devoted their lives to the decipherment of our current predicament, don’t deserve of us a somewhat more respectful consideration than simple rejection of their Anthropocenical-bullshit? Just because it’s going through memefication, turning into the Anthropomeme Braidotti pokes fun at, is it a reason to discard it or dismiss it? A meme gone viral shouldn’t interest us more instead of less spreadful material?

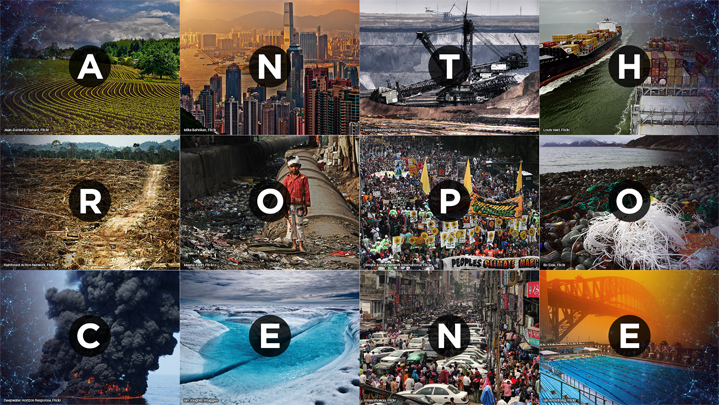

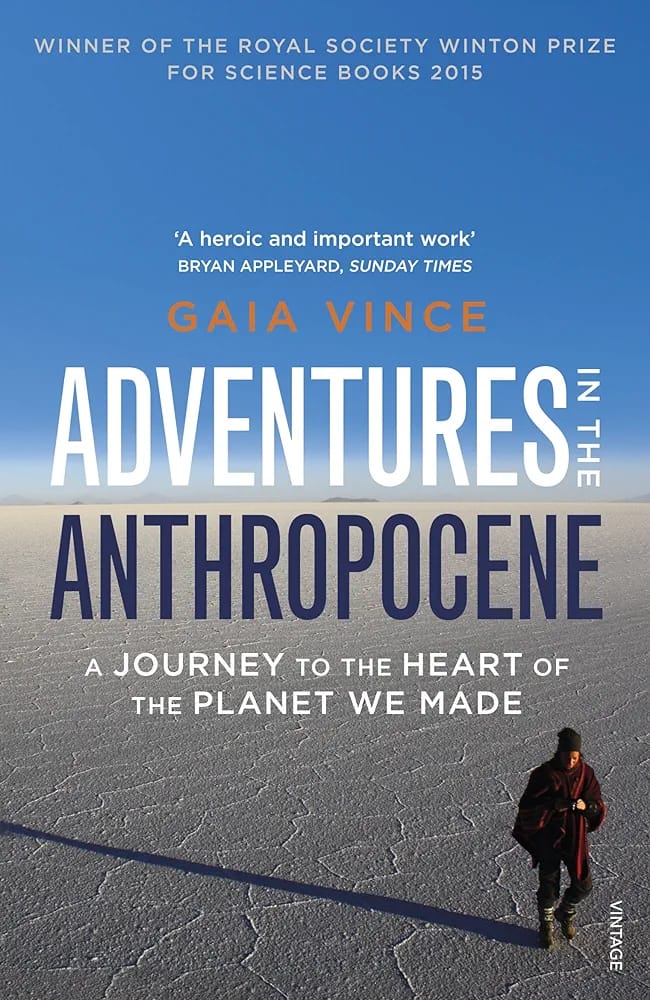

Gallery 1: Examples of books recently published whose titles or subtitles refer directly to the Anthropocene

Of course the Anthropocene is not a consensus, it’s a highly controversial term, and it’s quite funny (we might laugh along with Braidotti) to see the proliferation of the “cenes”, that is, of alternative proposals of names to baptize the epoch in geohistory we’re immersed in here-and-now. But this proliferation of names perhaps tells something else than the tale of cognitive capitalism and publish-or-perish academia trying to accelerate intellectual and artistic production around the Anthropocene’s axis. Perhaps this proliferation is proof that human agency as a transformer of geohistory is a fact too huge to ignore and that intellecuals and scholars can’t refrain from trying to interpret and critique, given the urgency of the global environmental crisis we’re facing.

Yes, perhaps we should find a better name and toss the anthropos in the garbage bin: Chtulucene is Haraway‘s proposal, Capitalocene is championed by Moore and Malm, and others speak about the Plantation Scene, the Technocene, the Necrocene – and I’ll leave it to pop-culture analysts to decipher what the heck Grimes meant by it when she made her album Miss Anthropocene. Of course that the Anthropocene, entering the distorting realms of pop culture, would end up becoming something quite different than what geologists are talking about, and this adds another layer of complexity to the matter.

Erle C. Ellis has written an excellent very short introduction to the Anthropocene, published by Oxford University Press (2018), and I’d like to propose here a thought experiment, or better, a mind game (which will be also an hommage to Lennon & Yoko). Imagine this: what if in recent human history, let’s say the last few centuries, even before the Industrial Revolution, we could gather enough evidence of a previous evidence of radical and sudden climate change brought about by human action (even tough not an action by all humans, just some of them), what would we conclude regarding our futurity?

Here’s what I’m talking about more concretely: the Conquest of America, taken as exemplary case, is surely an historical event of immense magnitude, and yet most of us are blinded to something quite crucial in its core: genocide and epidemics were followed by climate disruption. Here’s the evidence:

According to Ellis (2018), “the accidental ‘discovery’ of the Americas by Christopher Columbus set off a process of global social and environmental change like no other before, the Columbian Exchange… driven by European efforts to extract wealth from the Americas, human societies were integrated for the first time into a truly global world system of social, material, and biological exchange. All of these changes left evidence in the stratigraphic record, but one specific biological exchange stands out for its rapid transfomative effects:

The introduction of smallpox and other Old World diseases is estimated to have killed 50 million native Americans between 1492 and 1650 in epidemics of European diseases to which they had never before been exposed. The results were catastrophic, with whole societies collapsing in the face of rapid population declines of 50 to 90 per cent and more. Epidemics spread so rapidly through indigenous exchange networks that many native societies were wiped out before Europeans first reached them. Forced labour, resettlement, colonial violence, and imported slaves only accelerated the decimation. Before Europeans began transforming American landscapes into large-scale commercial plantations and ranches, the indigenous societies that had long cultivated crops and used fire to manage their vegetation had shrunk to a tiny proportion of their former extent. In their absence, forests began to regrow, taking up so much carbon in the process that they could have significantly reduced atmospheric carbon dioxide, an effect that may be evident in ice core measurements around 1610.” (ELLIS: 2018, chapter 5, pg 96)

Graeber and Wengrow also wrote about it in The Dawn of Everything in these terms: “There are those who place the origin of the Anthropocene rather, dating back to the end of the 16th century and start of the next. During this period there was a global drop in atmospheric temperature – part of the so-called “little ice age” – which cannot be explained by natural forces. Most likely, European expansion in the Americas had a role at that point with perhaps 90% of the indigenous population annihilated (out of a total estimated at 60 million inhabitants) as a result of conquest and disease infectious, forests have resumed in regions where terrace cultivation and Irrigation had been practiced for centuries. In Mesoamerica, in the Amazon and In the Andes, around 50 million hectares of cultivated land may have returned to be natural areas. Carbon absorption by vegetation has increased in scale enough to change the planetary system and trigger a period of global cooling driven by humans.” (GRAEBER; WENGROW: 2021, P. 282-283, quoted from the Brazilian edition published by Companhia das Letras)

This examplary case leads me to the following conclusions: we shouldn’t make the mistake of confounding the part with the whole, it’s not “the Europeans” (all of them) or “Europe” (as a name for a totalizing entity) that is responsible for the massive decline in Amerindian population; but of course the imperial enterprise spearheaded by some wealthy and powerful europeans brought about this “Little Ice Age” following the decimation of the natives of the continent afterwards baptized America.

This entails that it might be naive to blame the Anthropocene and global warming exclusively on the Industrial Revolution, when prior to it we have evidence of radical climate disruption connected with this “clash of the worlds” (“Old Europe” and “New America). Of course this nomenclature is also mistaken: we are in one planet, and there was no clash of two worlds, but an invasion of some humans on the territories of the continent where some 60 million human beings lived – a conquest which came grounded in an ideology of racism, slavery and theocracy.

It can also be said that the Little Ice Age was not an intended aim of the Europeans who invaded the territories they were intending to colonize and extract wealth from; it’s unintended consequence of the imperial enterprise, of course, and that’s quite tragic, but it doesn’t erase responsability and it doesn’t make the imperial enterprise any less accountable in futurity for the damage it has done. I’m sure most of the guys who came with Columbus and Cabral had no idea about microbiology and the dynamics of epidemics to predict that they were carrying in their bodies some germs as dangerous and murderful as their guns. But anyways these greedy ambitious europeans of imperial mind-set really did profit from genocide and slavery: who would be so naive as to believe the Industrial Revolution in Europe could have happened without the capital generated from the imperial plunder of America?

But another very important conclusion here is the fact: re-forestation could alter the earth’s climate with a cooling effect. When forests began to regrow, they absorbed CO2 in the atmosphere – and this very simples, unequivocal natural fact helps us tremendously to think about solutions for our futurity. Of course we’ll need to abandon fossil fuel burning and the hellish factory-farming pesticice-frenzy agrobiz model, but re-forestation is essential part of the solution of global warming. Why aren’t we shouting this more clearly on the streets and social media? Humankind must learn that to un-do the damage we’ve already inflicted in the Web of Life through the anthropogenic Sixth Extinction of biodiversity on the planet, we have to invent ways for the green to regrow, even if it means reducing our urbans sprawls, putting a sudden end to our junkielike addiction to petrol, plastic and concrete.

We must rewild, and that means much more than fighting fiercely for the protection of tropical forests (in territories nowadays located in countries like Brazil or Indonesia); it means re-forest instead of pressuring for further spread of urbanization and industrialization; it means extractivism of minerals (such as gold) must be brought to a sudden stop becaue it’s destroying tropical forests and killing Amerindian populations (such as the Yanomami in the Amazonia, which were victims of Bolsonaro’s genocide during the neo-fascist ecocidal rule of the far-right in Brazil [2018-2022]).

The so-called Anthropocene is a geological epoch where all life on earth is being damned to collapse or even extinction because of our accelerated production of manufactured wastelands. Re-wild and re-forest, which also means venturing into post-humanism and allowing flora and fauna other-than-human to flourish, are keys-of-action right now when we actually need the anthropos to step back, humble down and cool the fuck off.

Eduardo Carli de Moraes

Amsterdam, October 2023

BOOK DESCRIPTION

The proposal that the impact of humanity on the planet has left a distinct footprint, even on the scale of geological time, has recently gained much ground. Global climate change, shifting global cycles of the weather, widespread pollution, radioactive fallout, plastic accumulation, species invasions, the mass extinction of species – these are just some of the many indicators that we will leave a lasting record in rock, the scientific basis for recognizing new time intervals in Earth’s history. The Anthropocene, as the proposed new epoch has been named, is regularly in the news. Even with such robust evidence, the proposal to formally recognize our current time as the Anthropocene remains controversial both inside and outside the scholarly world, kindling intense debates. The reason is clear. The Anthropocene represents far more than just another interval of geologic time. Instead, the Anthropocene has emerged as a powerful new narrative, a concept through which age-old questions about the meaning of nature and even the nature of humanity are being revisited and radically revised. This Very Short Introduction explains the science behind the Anthropocene and the many proposals about when to mark its beginning: the nuclear tests of the 1950s? The beginnings of agriculture? The origins of humans as a species? Erle Ellis considers the many ways that the Anthropocene’s “evolving paradigm” is reshaping the sciences, stimulating the humanities, and foregrounding the politics of life on a planet transformed by humans. The Anthropocene remains a work in progress. Is this the story of an unprecedented planetary disaster? Or of newfound wisdom and redemption? Ellis offers an insightful discussion of our role in shaping the planet, and how this will influence our future on many fronts.

READ ON

REFERENCES

BRAIDOTTI, Rosi. Lectures in YouTube:

MALM, Andreas. https://www.filmsforaction.org/articles/the-anthropocene-myth/

ELLIS, Erle C.. A Very Short Introduction to the Anthropocene. Oxford, 2018.

GRAEBER AND WENGROW. The Dawn of Everything / O Despertar de Tudo. Companhia das Letras, 2022.

Publicado em: 14/10/23

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes