KATRINA BABIES: Como a arte pode construir resiliência em face do Capitalismo de Desastre

<Eco-trauma> should be a trending topic. It deserves a hype as high-reaching as <Barbennheimer>. And yet it’s far away from the spotlights of mainstream culture most of the time: trauma doesn’t sell tickets like Avatar. No film or album is topping the charts with protagonists suffering from ecological grief or climate anxiety. Art dealing with trauma tends to be unpopular or extremely limited in its scope, consumed by a niche: there’s no box office super-hit dealing with Disaster Capitalism as a traumatizing machinery.

Perhaps that’s slowly changing, due to the repercussion of Bong Joon-Ho films, for instance. We can also feel the resistible ascension of radical cli-fi about violent action against what’s causing the eco-traumatization: <How To Blow Up A Pipeline>, a book by Andreas Malm and a film by Goldhaber inspired by it, being perhaps the best of recent artworks that encapsule this. But it’s still a matter looming on the underground and on the fringes of our dominant culture. In Academia, however, the theme is gaining momentum.

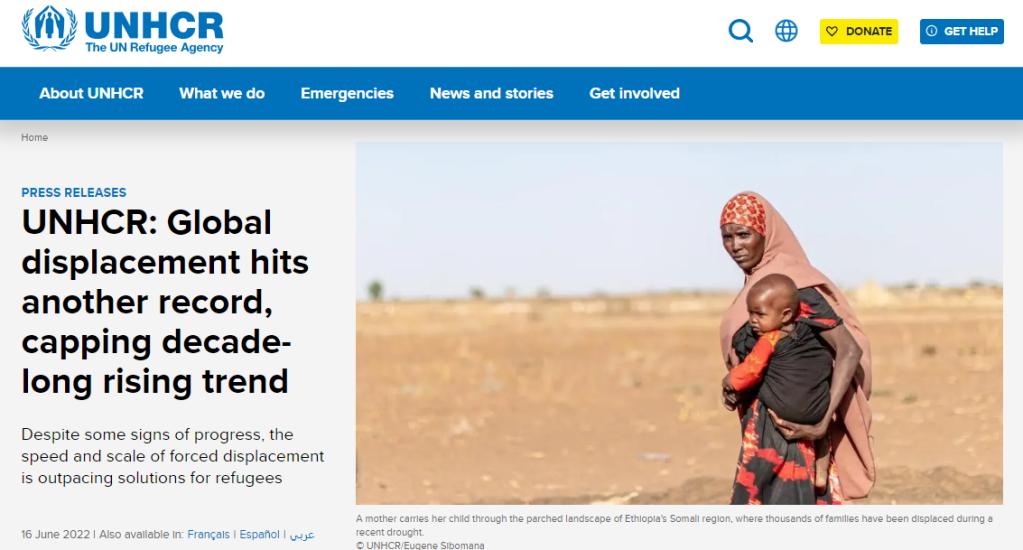

Most of us have heard we’re living through the <worst refugee crisis since World War II>, and that it correlates to climate disruption. Many of us can’t afford to care about global warming and its effects upon society, but those who are careless, and those who are choosing irresponsably the path of self-blindness, will also get hit by hurricanes. There’s no easy escaping from the whirlpools of climate extremities in the Anthropocene, even tough the wealthy dream on their Muskian dreams of running away to colonies in Mars, or enjoying their skyscrapping bunkers high above the toils of the Bangladeshi population – or even of future Amsterdammers and New Orleans residents… – who’ll be fleeing places headed to become like several new-born <Atlantis>.

The <United Nations> points out, concerning the refugees of the world (many of them also eco-traumatized, as the Syria-case states): “by the end of 2021, those displaced by war, violence, persecution, and human rights abuses stood at 89.3 million, up 8 per cent on a year earlier and well over double the figure of 10 years ago, according to UNHCR’s annual Global Trends report. Since then, the Russian invasion of Ukraine – causing the fastest and one of the largest forced displacement crises since World War II – and other emergencies, from Africa to Afghanistan and beyond, pushed the figure over the dramatic milestone of 100 million.”

This is eco-trauma on massive scale – and we all have recent memory of the Covid-19 pandemic to remind us of the extent and magnitude of the ecological crisis we’re immersed in. (Yes, of course the coronavirus outbreak was caused by eco-devastation and not by the malignant will of a virus…)

Eco-trauma is here and it will be even more present in future years. And yet geopolitics in the so-called “First World”, I mean public policy and citizenship in the “well-developed nations”, is often stuck in matters concerning how the wealthy nations can defende themselves from the invaders by building Trumpian walls, or by creating segregation and exclusion by the abuse of the principle of censitary privilege and rentism.

The moneyfull get a high-class cruise with caviar and cellos in this sinking Titanic, while the masses of the poor and desinfranchised get shot at by police, or imprisoned for being sans papiers by the repression forces. Police, Prison, Army etc. are the institutions that are often being appointed as the right and appropriate “social arms” to deal with refugees – and it sounds absurd to my ears: why not people from the fields of Education, Health, or Arts and Culture, for instance? Why is it we treat eco-trauma and climate refugees as matters of police and not psychology, imprisonment and not therapy?

Far-right populists thrive on xenophobia, and even relatively privileged, middle-class people defend themselves inside the gates of private properties that start smelling evermore like little bunkers. And we end up having a shallow or non-existent public debate about how we’ll deal wisely with a social phenomenon that won’t simply go away – worst, it’s bound do escalate: the traumatized by the ecologial crisis that the Capitalocene has brought about escalate while we seem to have diminishing resources to capacitade us to deal with that in the troubled field of our turbulent psyches. How can mental health and psychic healing be collectively ensured to all those in need of it?

We shouldn’t view the “eco-traumatized” person as some sort of abnormal creature, as an exception to the rule. Not only because the numbers of eco-traumatized people gets rising up in direct proportion with rising see levels. But also to avoid the attitude of paternalistic pity: oh, poor eco-traumatized fellas! Let’s buy’em some lollipops and give to them as charity! No! Eco-trauma is an experience that can make its “victim” refuse the status of further victimhood and choose the path of activism, of joining forces with others who have been also traumatized by Disaster Capitalism.

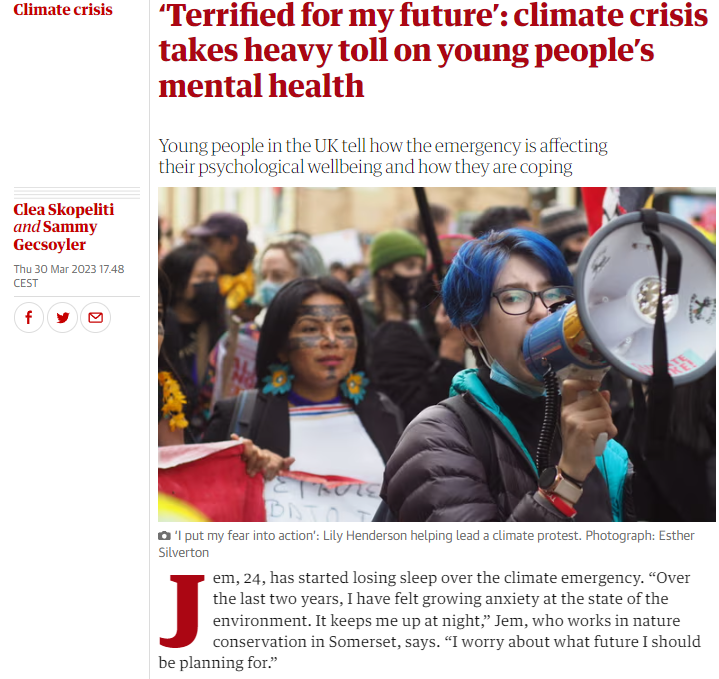

Eco-trauma can mean an awakening, and I admire the clarity of thought of Jem, 24, who told The Guardian:

– I am on antidepressants but I don’t think this is a solution. Things like antidepressants can’t fix things when it’s an external problem. It’s the world we have created that is causing these issues.”

“In a recent survey by the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), almost three-quarters (73%) of 16- to 24-year-olds reported that the climate crisis was having a negative effect on their mental health, compared with 61% of all people in the UK.”

I endorse Garreth Morgan’s opinions. Eco-trauma shouldn’t be treated in the individual field, it can only be dealt with as a collective dilemma. It’s a psychic sphinx that will escalate in our future, it will spread all around our culture. Eco-trauma, I mean, is a matter that should concern us in the present tense, of course, but it’s also one of those factors we can be quite reasonably sure that will make it into our futurity with lot of weight. The future of eco-trauma in this planet of ours is bound to weight gigatons.

Given the magnitude of the menace, the breadth of the threat, are we reasonably discussing theraphy, and how it can be provided, in order to help heal the traumatized? Are we preparing to assist the eco-traumatized with mental health issues beyond the fallacy of medicalization as panacea? Are we ready to have a mature conversation also about psychedelic treatment for all kinds of post-traumatic stress disorder, including those caused by environmental catastrophes?

Yes, “there will be blood” (and trauma), as the title of P.T. Anderson‘s film stated, as long as “black gold” extraction, for example, keeps on happening in a world whose directions are still sadly dictated by Shells (from Hell) and other fossil fuel burners. And we are going to need artists to step in the scene with their artworks not only to depict the catastrophes that traumatize us, to criticize the forces and powers that caused them, but also to help out in some sort of healing process that needs to be done also artistically.

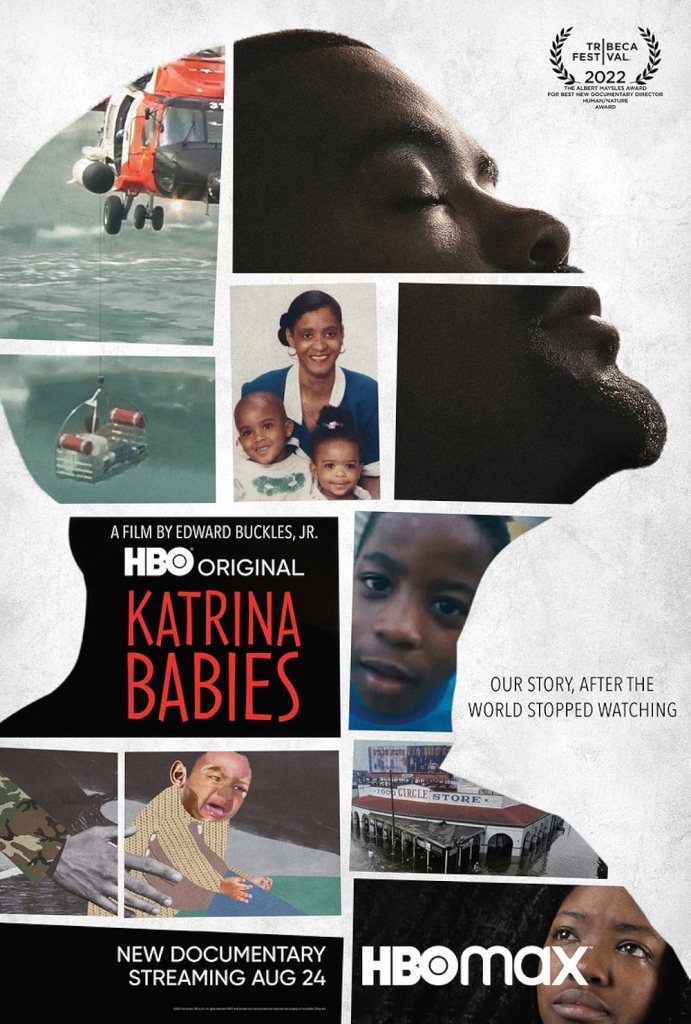

That’s one of the lessons I deem to have learned by watching Katrina Babies, the HBO-produced documentary “from first-time filmmaker and New Orleans native Edward Buckles, Jr.” which “offers an intimate look at the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and its impact on the youth of New Orleans. Sixteen years after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, an entire generation still grapples with the lifelong impact of having their childhood redefined by tragedy. New Orleans filmmaker Edward Buckles Jr., who was 13 years old during Katrina and its initial aftermath, spent seven years documenting the stories of his peers who survived the storm as children, using his community’s tradition of oral storytelling to open a door for healing and to capture the strength and spirit of his city.” (HBO.COM)

The film suggests that New Orleans can only be healed after this massive eco-trauma if we refuse what Naomi Klein called The Shock Doctrine, the onslaught of neoliberal capitalism using the disaster as opportunity for rebuilding the city with privatization and gentrification running amok. Katrina Babies is a collective and plurivocal manifesto of Afro-americans, a denounciation of the plight suffered by blacks during this very racially unequal tragedy which befell much more terribly the poorest and most oppressed part of the population.

Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts, from 2006, is also an excellent historical document in film form about this traumatic event – and it’s also smartly bursting with insight in all things concerning race matters. But Katrina Babies does not repeat the Spike Lee joints, it isn’t redundant, especially because it decides to portray and give the power-of-the-word to those black kids and adolescents who felt in their flesh the impact of that terrible storm.

The poster of the film includes a provocation: “our story, after the world stopped watching.” We watched New Orleans for a while, and then our short-attention span reclaimed our focus, we looked elsewhere – we trying to pretend Katrina didn’t leave behind a trail of trauma of stratrospheric proportions.

Disaster can also be turned into a spectacle. It can sell newspapers, pump up the audiences of breaking news programs. Disaster movies have taught us that catastrophic scenarios can thrill us, can generate in our hearts and minds very deep and profound commotions, and many os us are ready to pay for a ticket or a stream which provides us with delightful disasters. But Katrina Babies refuses to commodify the catastrophe and chooses rather to be an oral symphony for the eco-traumatized – almost them, in this case, also traumatized by racism.

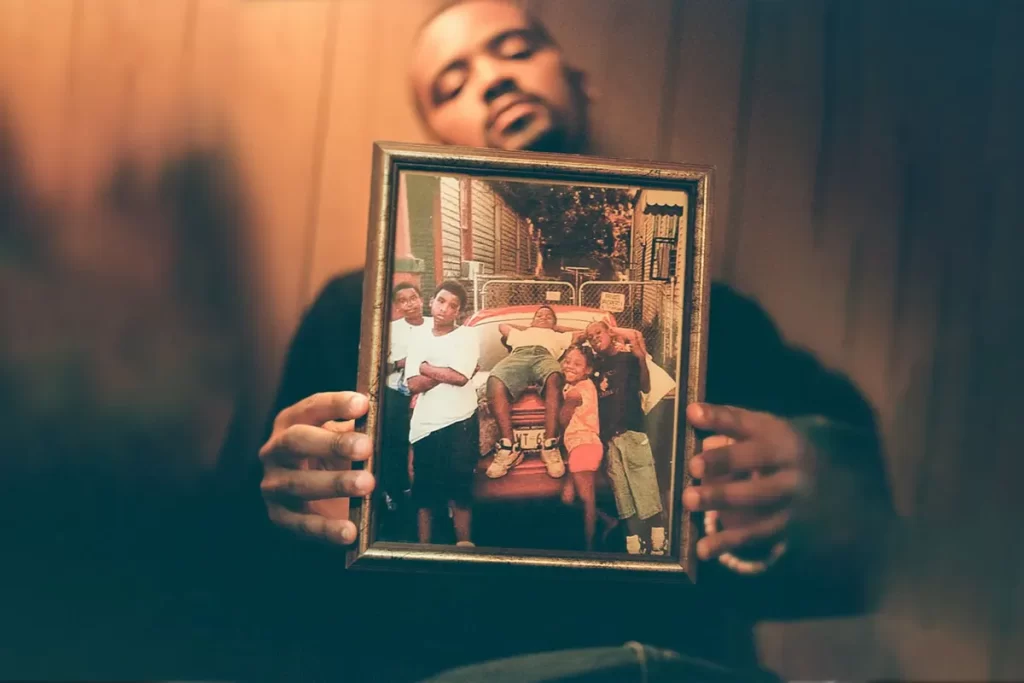

These are people who feel that telling the tale of their trauma is a path to healing themselves. To talk about their vulnerability, their bruises, their losses, their scars, is a necessary step towards a possible cure also for the bruised territory that will never be the same after August 2005.

The film portrays documentary filmaking as a social space of seminal importance because it offers the Spielraum, the “running-room”, for storytellers to tell their tales – full of sound and fury, of course. Edward Buckles Jr. has made more than a good film, he has propposed some sort of social movement mediated by cultural production: making a film together as a means to heal together. And he ends the film letting the protagonists ensure the spectators that to tell the tale of our misfortune has been therapeutic, but… it’s also true that therapy has its limits within a society that keeps following a track that will lead to more and more escalating eco-trauma. It’s greedy, productivist, consumerist, fossil foolish society that needs badly an urgent therapy.

This film-essay has an author, who is quite clear about his locus of speech – born and raised in New Orleans, and one of the “kids” (or babies) who suffered Katrina in his flesh when he was barely a teenager, so it can also be read with the key of auto-biography. Katrina Babies collects fragments of autobiographies by the New Orleans eco-traumatized.

Buckles ends the film rappin’ about resilience. He doesn’t want resilience to become some sort of fake happy ending to this dark, sobering tale. “Even tough we are resilient, we can never get back what was lost.” This amazing, resonating phrase goes deep: some irreversible damage has been done, can’t be undone. Eddie Buckles ends the film saying that there was a loss that can never be healed or repaired. Tragedy.

Something in New Orleans is broke beyond repair, let’s avoid fooling ourselves – and there are traumas that won’t get healed, there are bruises that will lead only to suffering and death. Don’t let the fake certitude of resilience’s triumph push us into the barren terrain of toxic positivity, of bullshit cruel optimism. The filmmaker and his comrades have just shown us eloquently, through the aesthetic means of this film, by delivering us the collective gift of Katrina Babies, a film that knows how to sing its blues, how much vulnerability, how much brokenness beyond repair, how much tears over unrepairable losses lie at the core of such difficult and troubled resiliences which the survivors of Katrina attempt to embody.

Eduardo Carli de Moraes

Amsterdam, September 29th 2023

Published in Awestruck Wanderer & A Casa de Vidro

LEIA TAMBÉM: Salon.

Publicado em: 29/09/23

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes

1 comentário

E aí, pessoal! Como alguns de vocês já sabem, neste mês de Setembro, em virtude do início do período “sanduíche” do meu Doutorado, mudei pra Amsterdam e comecei a realizar, com bolsa da Capes e apoio da FAFIL/UFG e do IFG, um período de 6 meses de pesquisa na Universitat van Amsterdam (UvA) onde estou afiliado à “ASCA” (Amsterdam School For Cultural Analysis). Minha produção no campo da crítica cultural e da filosofia da arte, nestes meses, vai ser sobretudo em língua inglesa devido às demandas de comunicação, colaboração e interlocução com meus pares/peers aqui nas Nederlands. O plano é que o site d’A Casa de Vidro seguirá com publicações frequentes, mas no meu caso elas serão em inglês e, na medida do possível, irei providenciar também os artigos em português (hoje em dia, as I.A.s e os Googles Tradutores ajudam muito a acelerar estas traduções-traições). Eis aí o primeiro artigo que pude produzir aqui e que se insere no campo temático que tenho investigado: o cinema do “eco-trauma” e o modo como a distopia-real da catátrofe climática tem sido tratada pela 7a arte. Neste artigo, falo do filme “Katrina Babies”, documentário produzido pela HBO e dirigido por Ed Buckles Jr. Abraços a todes do já-com-saudade e temporariamente- Amsterdammer… – Carli.

ACESSE O HIPERTEXTO MULTIMÍDIA: https://acasadevidro.com/katrina-babies/

Eduardo Carli de Moraes

Comentou em 29/09/23