MONSTERS OF OUR OWN CREATION: Distopia in film portrays possible wastelands to come

Like a doctor using a stethoscope to listen into the patient’s body, let’s pay attention to our cultural mainstream, to the comtemporary artistic zeitgeist, to listen to the monsters within it. By doing so, by which I mean by experiencing the greatest possible variety of artworks that contain monstrosities (including those in Cronenberg, Lynch, Wes Anderson etc.), we might hear, as a blastful statement made into our ears (amplified by the stethoscope of critique): distopia is on the rise. And so are the sea levels. And so are the bloody wars. Monsters all around, most of them of our own making.

Who is surprised to witness that, in such an epoch, Godzillas would be roaring? Who is amazed that our culture is infested with kaijus? Damned Godzillas, roaring for years, making sounds similar to T Rexes in Spielberg’s Jurassic Park – this is the sound distopia makes when it descends upon thousands of screens, in cinemas of thousands of cities. Mass destruction in fiction can feel like an amusement park. Disaster movies sell. We wanna buy distopia.

Rising up and blooming lushly in the Garden of Culture, worldwide, the realm of distopia widens, expands its grip upon our imagination and our arts. It would seem that the territories claimed by distopia, or conquered by it, are ever increasing, while utopic imagery seems to be lacking. Take, for instance, the fact that the history of the 7th art offers us proliferation of monsters capable of massive destruction – to mention all of them would make us reach the lenght of a book. Something probably has been written and must be called something like The Bestiary Of Modern Cinema: An Atlas Of Monstrosities. For a real book, and not an hypothetical one, refer to <Taschen’s Horror Cinema>, “a chilling volume packs 640 pages full with the finest slashers, ghosts, zombies, cannibals, and more, curating the very creepiest screen creations from the flickering spooks of the 1920s to the special-effect terrors of the 21st century.” (DUNCAN/MÜLLER)

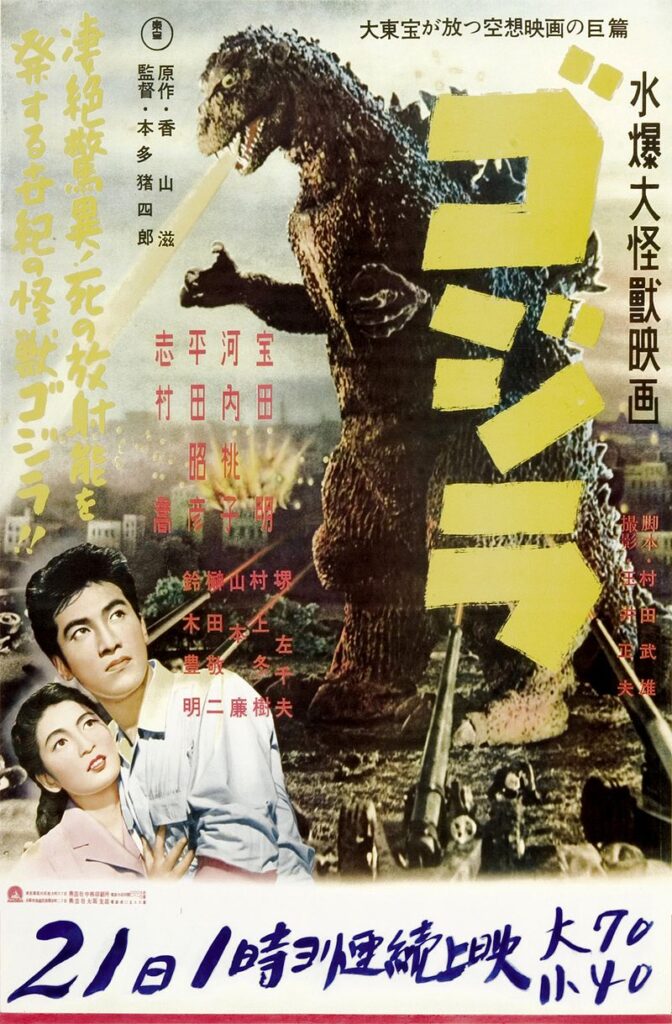

Especially during The Great Acceleration period, from mid 20th century onwards, when the so-called Anthropocene gains momentum, the monstrosity is often shown to be of our own making. Man-made monsters flood the big screens. It signals, to quote a line from the very urgent and clever song by the Brazilian rock band Legião Urbana, that “we’re lost amidst monsters of our own creation” (“Estamos perdidos entre monstros de nossa própria criação”, In: Será, 1984). This is clearest of all in the cultural phenomenon Godzilla.

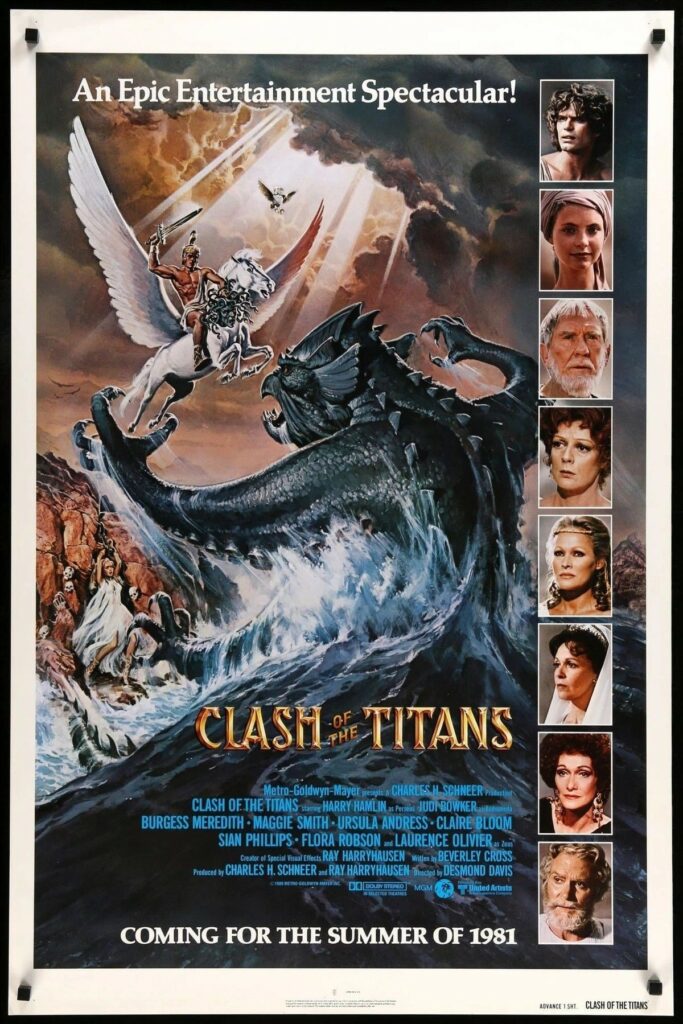

It is cinema’s most prolific and long-running franchise – and not only in the monster business. Nowadays, <38 movies have been made with Godzilla in it>, …Minus One being the most recent release, and it all began in 1954 with Ishiro Honda’s Gojira. Gabriel Solomons, writing for the magazine <Beneficial Shock!>, in a piece called Size Matters, has highlighted something that makes Godzilla stand out, being distinctive from other colossal and monstruous creatures of the screen (such as the Kraken, in Desmond Davis’ 1981 Clash of Titans): the Japanese Godzilla

“resonates due to his being rooted in real human tragedy – that of a nation decimated by nuclear holocaust, seeing in him the starkest reminder of the damage that science and technology can unleash when put in fragile human hands.” (1)

SOLOMONS, Gabriel. Size Matters. In: Beneficial Shock!, n. 8, 2023.

This is what happened to Japanese cinema in the 1950s: it was living still under the impact, the resonance and the radioactivity spread from the blasts of nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This context of collective tragedy brought to the big screens that famous monster of the Pacific Ocean that has both a superdestructive super-power (the rays he’s able to deploy have the potency of atomic weapons – he’s the evolved version of the mythical Dragons capable of spitting fire) and a completely irrational behaviour.

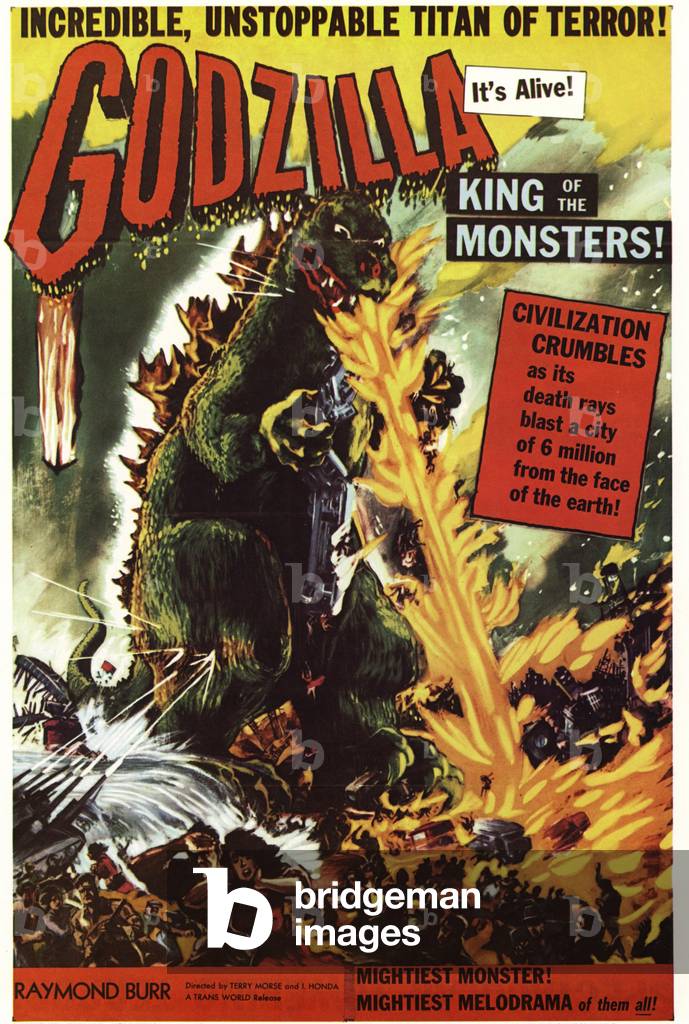

You can’t possible reason with a Godzilla, you can’t talk him into kindness and compassion. It’s indifferent to human lógos, our words are completely useless against it. We don’t talk the same language. Far worse: the beast only understands differences of force, its stupid brutality seems to be only vanquished by a counter-brutality. In its bestiality, the mega-beast is quite capable of wiping out a city of 6 million people – without dropping a single crocodile’s tear. A poster for Honda’s 1954 film, quite symptomatically, says the Godzilla could kill 6 million people with his “death rays” – it could produce an instant Holocaust. Godzilla could become far worse than the Third Reich – who needed some 6 years to produce the massive deathtoll of the Shoah. Godzilla could be Hitler on steroids, a frantic and a-logical dinosaur, awoken from the catacombs of natural history, arisen because of our deployment of the infernal fire of atomic weapons.

In her very interesting book about Fear – A Cultural History, Joanna Bourke deals extensively with nuclear threats and underlines the theme of pollution: “The polluting aspects of the nuclear threat became a common theme in fiction and films depicting the future, most famously in the case of Godzilla, a prehistoric monster resurrected as a result of H-bomb experiments.” (BOURKE, London: Virago, 2005, p. 258)

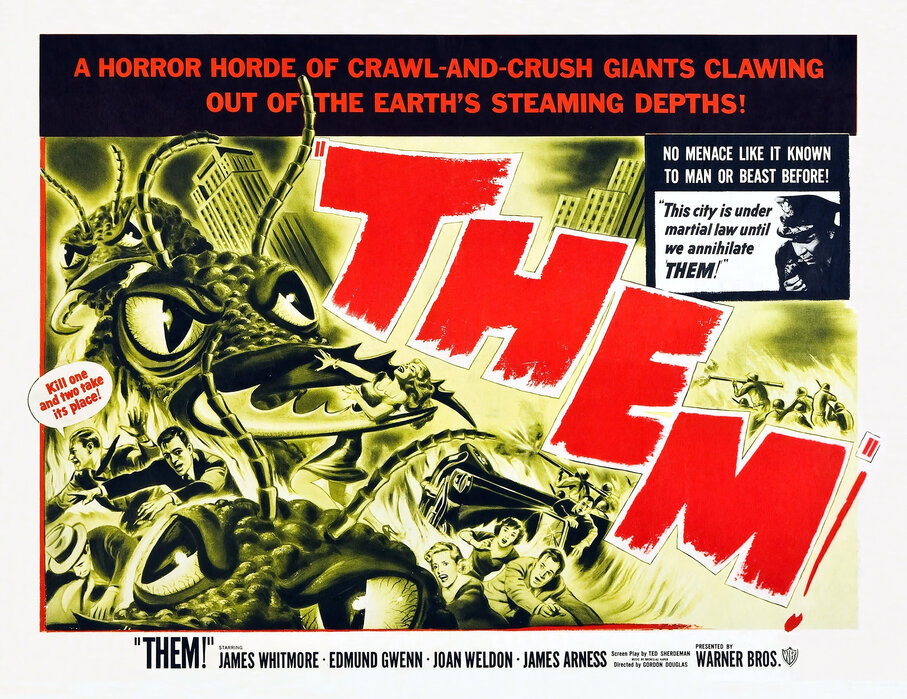

She also calls our attention to the fact that novels from the 1950s also depict the poisonous infections brought by the un-chaining of the nuclear Prometheus, and remembers us that in 1954, when Godzilla was released, the biggest hit in the box-office was Them!, a film that participates in the same context of justified paranoia about a possible nuclear holocaust if the so called Cold War happened to heat up:

“Novels like Margot Bennett’s The Long Way Back (1954) included plants rendered carnivorous by nuclear poisoning, while Tyrone C. Barr’s The Last Fourteen (1959) had one of the fourteen survivors of a nuclear war being killed by a giant featherless duck. Radiation was portrayed as the invisible enemy, silently infecting everything in its path. In Them! (1954), the biggest grossing film of that year, the pollution brought about by radiation was explicitly linked to Cold War communist threats.

When the military eventually took action against the killer ants, a journalist asked, ‘Has the Cold War gotten hot?’ The film ended ominously after the destruction of the giant ants, with the following exchange:

Graham: If these monsters got started as a result of the first atom bomb in 1945, what about all the other ones that have been exploded since then?

Medford: When man entered the atomic age he opened a door to a new world. What we’ll eventually find in that new world nobody can predict.

Fears about generals, scientists, super-computers and terrorists were a staple in this genre, as was the argument that nuclear war was simply an inevitable consequence of paranoid Cold War animosities.” (BOURKE: op cit, 2005, p. 269)

Looking towards the rearviewmirror to the year that has just ended, 2023, it’s astonishing to notice how much massive destruction by atomic weapons became a major theme – and not only because of <Nolan‘s Oppenheimer>, which became a film of tremendous boxoffice sucess (headed to 1 billion dollars), but because of the return of Godzilla, in December 2023, with <Takashi Yamazaki‘s Minus One>. I mostly agree with the excellent remarks by <Bela Eischler in her Futurices episode> dedicated to the film, but I would highlight more strongly this element: the protagonist of the film starts off as a kamikaze pilot that is troubled about his tasks as a soldier and he’s no longer willing to sacrifice himself in a war.

But social context weights heavy on our individual will – and the protagonist keeps getting sucked into situations that turn him into a kamizake machine – even tough he seems unwilling to give his life to the supposed greater good of those who will benefit from his deed (which is the deed-of-his-death). The core of Godzilla Minus One is a discussion about the behaviour of risking yourself to an extent that you reach almost near-certain death in order to achieve, through self-sacrifice, something that might be good to the collective, the nation, the army. The human war has ended (WWII is History…), but war will rage on. ‘Cause you can’t fucking erase the scars made in a nation, a territory, a Nature, by atomic blasts. In the wasteland that Tokyo has been turned into, where a young woman rescues a orphaned baby and raises it, the rubble of the previous war is still to be cleared and a new monster is already on the loose.

Godzilla can’t give the protagonist the luxury of peace after World War Two. The symbolic meaning of such a film is both historical (in the sense of a statement about the past) and cultural (a statement in the present tense, and that changes it by its apparition and expression). It obviously corelates with History – 1945’s devastation of Japanese territory by the H-bombs made in USA (and dropped also by the lovely Yankees…). But it also corelates with contemporary culture’s tropos towards distopia.

2023 shows, also throught the re-entry on the scene of <The Hunger Games (Lawrence’s The Ballad Songbirds and Snakes)>, but also through the joint venture Godzilla Minus One + Oppenheimer, that distopia is among us, roaring loudly, asking us to worry about atomic weapons and massive destruction by technological means and by monstruous deeds. The beast is alive and kicking: the icon of Godzilla, this very strong specimen – a loud beast, frightening, hard to beat, highly destructive atomic-age monster, still makes us run to buy tickets for the screenings! It goes to show that disaster movies are still a hype. It perhaps will be increasingly so – because of course capitalism can make some profit out of the apocalypse it has generated and which he is now bent on accelerating.

The Titanic of our current, “normal” industrial civilization is sinking fast. It has been damaged not only by icebergs unforeseen but also attacked by new atomic monsters, new awakened dinossaurs, threatening us with extinction because of our previous vices, crimes and screw-ups.

In 2016, the 31st film of the Godzilla franchise that had been kickstarted in 1954 by Ishiro Honda, reached the movie theathers in Shin Gozilla, by Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi. Writing for Beneficial Shock!, George W. Stewart states that “instead of following only Godzilla’s destructive path, the audience is led through the corridors of politics and scientific offices, witnessing strategic discussions.” (STEWARTS, 2023, p. 10)

This is true: Godzilla, in his 2016 and also in his 2023 re-incarnartions, became more geopolitical, more attentive to historical context, more interested in the human affairs concerning war strategies to defeat the monster, which is superior in physical strenght, but that be beaten and vanquished through the use of human collective intelligence and endeavour etc.

The possibility of a happy ending is also sold into the package of this apocalyptic merchandise: capitalist consumer culture knows well how to frighten us but also to confort us with some candy for the anguished mind. The beast can be vanquished by united humans with very powerful weapons of mass destruction! We can, for example, encircle the beast, put in chains, and then drag it to the bottom of the ocean, and then quickly bring it up again, using pressure as a weapon: ha ha, Godzilla will get fucked by the bends! Human triumph despite all the beast’s destruction is sold to us as the most probable ending to the carnage.

But let us not be easily bought by the cheap thrill of a happy end. An animal such as ourselves, that invented atomic weapons, and in whose History Hiroshima/Nagasaki, Chernobyl, Fukushima, Bophal etc. were all events that happened, can’t possible rest serene in the faith that all will end well. The creeds of naive optimism are forbidden for a mind deeply trained in distopia. Here, in this realm, fiction teaches life something crucial.

Distopias portray in fiction the wastelands that might come. It’s all about possibilities of the worse, depicted in a big screen, in order also to provoke in us the desire to avoid the worst-case-scenario fictionaly depicted. In recent Godzillas, we get sold the ideology of victory of the humans over the Beast by collective endeavour – and the promises of reconstruction. This is distopia sweetened by sugary merchandise. It’s logical within our emotional landscapes: we buy tickets for the disasters and wastelands but also for the ear candy of promised redemptions and reconstructions.

To fear Godzilla, to be “happy” when the humans kill the monster etc., are phenomenons that should make us ponder upon this mystery: what does it mean to fear fictions, and then to be rewarded afterwards with a solution to our anxieties? What’s the function of fear in fiction, and why do we as audiences get hooked in it? Why do we pay to be terrified by horror films, why do we keep on buying Godzilla tickets for more than thirty (30!) fucking films thoughout the decades? What could be the relevance of fearful affects such as those evoked / provoked by Godzilla, Oppenheimer, Hunger Games? (To name just a few of 2023’s distopian artworks of highest profitability for cultural industry). It seems to me that when facing these kaijuns, we’re facing through the fearing a monster created by our own hybris; we are depicting through the monster what in Greek myth and thought is the nemesis.

Inside the cinemas, through the process of fearing fictions, we try to elaborate our structure of feeling and of perceiving the world into a shape that’s increasingly being culturally enformed by this: distopias on the rise; distopias proliferating; distopias making it impossible for Thom Yorke’s melancholy-ridden lament asking for “no alarms and no surprises” to be answered. His call is nowadays severely dis-respected. Alarms are sounding all the time in Gaza or Ukraine announcing air strikes and people dead under the rubble. Alarms are also sounding in the IPCC reports and UN’s COP’s Climate Talks. Alarms and surprises abound – and most surprises are scary – covid19, for instance.

Disaster movies and distopic scifi can always be accused by detractors of being un-productive and uselessly pessimistic – as if they would produce only fatalism through their alarmist content; as if it would only depress people with these games of mutual slaughter and this invitations for “meet-ups at midnight at the hangin’ tree”. But this is shallow and untrue: distopia speaks some truth about our collective life as human species, and fearing fiction can also teach us some wisdom.

The real genius in the cinema of monstrosity will not be found in Godzillian or Hungery Games territory. These films are very important cultural symptoms, but they’re also filled with cheap thrills, they’re also capitalist crap sold in the culture market. In my perspective, the genius in the aesthetics of monstruous dystopias lies elsewhere: of course, in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and its resonances (from Whale to Branagh); in Bong Joon Ho‘s The Host, Parasite and Snowpiercer; in Cronenbergian body horror (in classics of the genre such as The Fly, the Brood, Shivers, Videodrome); in Lars Von Trier‘s Dogville and Manderlay; in Fleischer‘s extremely prescient Soylent Green; and of course in Stanley Kubrick‘s masterpieces in the history of distopian artforms: A Clockwork Orange (inspired by Burgess’ novel) and Doctor Strangelove. Godzilla is a simple, unidimensional monster when compared to the complex and still terribly frightful monstrosities – once again: mostly of our creation – that abound in these manifestations of distopia-in-art.

Eduardo Carli de Moraes

Amsterdam, NL

January 2024

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOURKE, Joanna. Fear: A Cultural History. London: Virago, 2005.

DUNCAN/MÜLLER. Horror Cinema. Taschen, 2024.

EISCHLER, Bela. Futurices Episode: Godzilla Minus 1. YouTube, 2023.

SOLOMONS, Gabriel. Size Matters. In: Beneficial Shock!, n. 8, 2023.

STEWART, George W. Shin Godzilla. In: Beneficial Shock!, n. 8, 2023.

WIKIPEDIA. Kaiju. Consulted in 2024.

FILMOGRAPHY

Main films mentioned here:

Gojira (1954)

Them! (1954)

Shin Godzilla (2016)

Godzilla Minus 1 (2023)

Oppenheimer (2023)

Hunger Games: Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes (2023)

READ ON… SUGGESTED FURTHER READING:

SPREAD YOUR LOVE LIKE A FEVER: SOCIAL MEDIA SHARING >>>

MONSTERS OF OUR OWN CREATION: Distopia in film portrays possible wastelands to come. About Godzilla Minus One (2023) @acasadevidro: https://t.co/oYfShHZ9ia #scifi #Godzilla #MonsterMovie

— A Casa de Vidro (@acasadevidro) January 22, 2024

Publicado em: 21/01/24

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes