The aesthetics of the absurd and love’s profane mess in Kaurismaki’s “Fallen Leaves” (2023)

Savour the irony in David Lynch‘s proclamation: “what a great time to be alive if you love the theather of the absurd!” It tastes similar to another punchline by Woody Allen: “Life is full of misery, loneliness, and suffering – and it’s all over much too soon.”

Both phrases sound funny and witty because the absurd isn’t usually seen an object of desire, and yet both Lynch and Allen are saying that it’s possible to desperately love life, with all it includes of “misery, loneliness, suffering”, if only you acquire a taste for “the theather of the absurd”. If you acquire a taste for life’s absurdity, you might reach the end of this messy samsara and still lament that “it’s all over much too soon”.

If you manage to learn how to love life not because it’s delightful and filled with pleasure (that would be a way too easy task to accomplish, and the cosmos will now allow us that privilege), but in a tragic disposition, in which you love it knowing and feeling it includes the horror and the cruelty mixed with empathy generosity, in a difficult-to-stomach mixture of “all the beauty and the bloodshed” (as Laura Poitras and Nan Goldin might have put it), then you might be on the right track to a trembling, bittersweet, tragic-comic delight in existence.

Then, the absurdities of life are no longer a reason to hate it, despise it or attempt to annihilate it through suicide – the absurd can make us laugh, the dissolution of meaning can cancel heavyweights on our backs, and the wonderfulness of aliveness can be cherished even in the presence of nonsensical horrors, frustrated ambitions and broken promises.

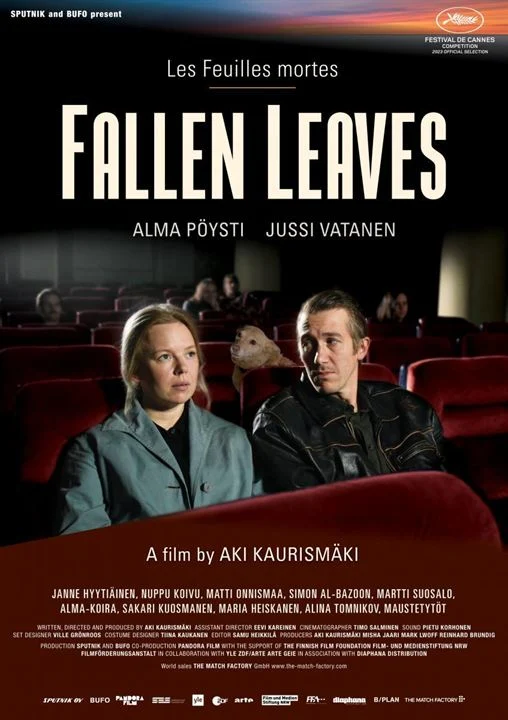

After watching Fallen Leaves (Kuolleet Lehdet), one of the greatest films released in 2023 (Winner of the Jury Prize at Cannes), it felt obvious to me that the Aesthetics of the Absurd is alive and kickin’ also in the cinematic art of Finnish filmmaker Aki Kaurismäki. His slice-of-life films are definitely not made as crowd-pleasers or eye-candy: to savour a trip through Akiland, as critics are always telling us, we need an “acquired taste” (Cf. Senses of Cinema).

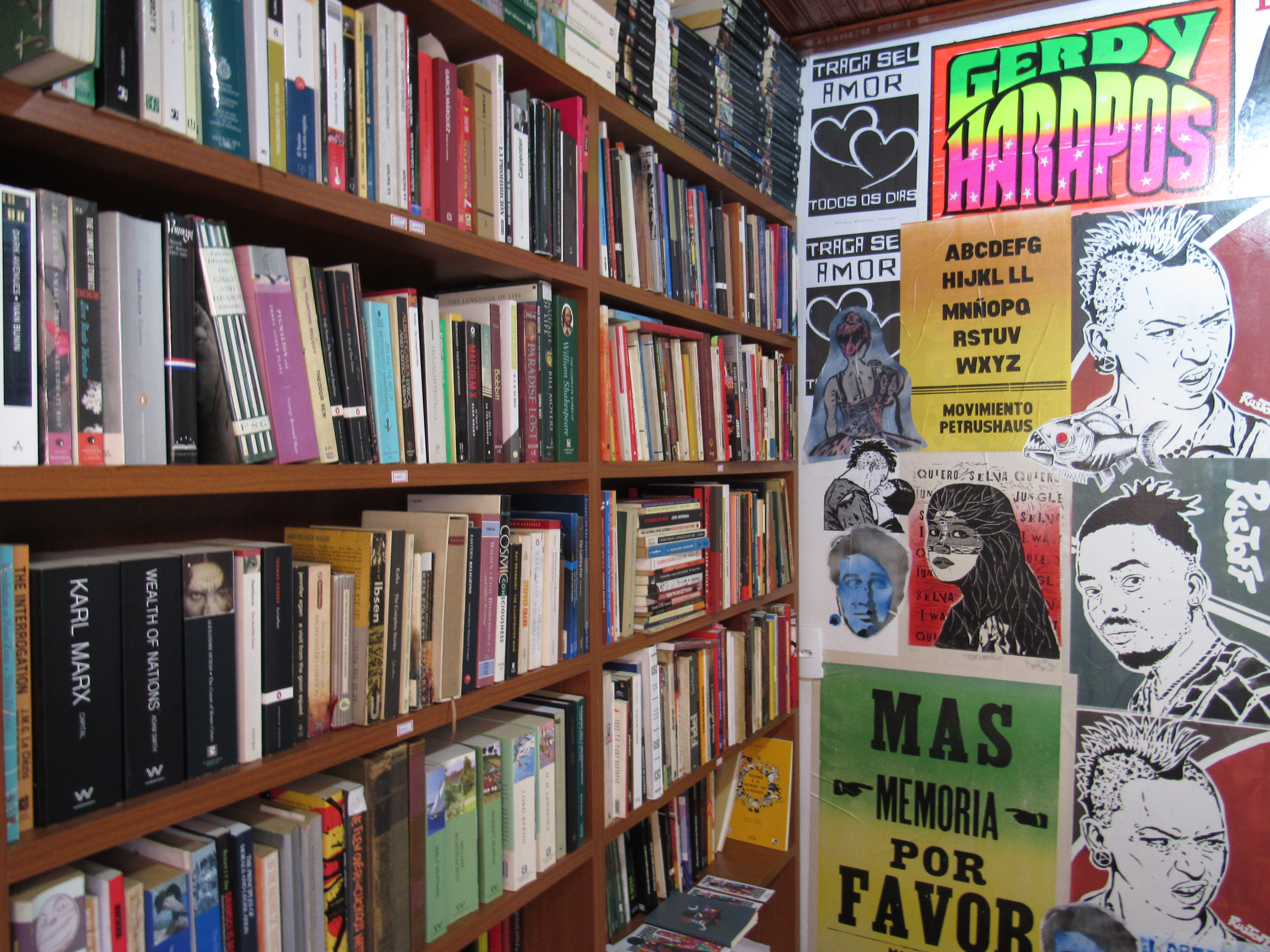

I’ve acquired a taste for Kaurismäki and I’ve left the Kriterion in Amsterdam, after the screening, feeling delightfully in love with this absurd life of ours. This film may seem like an attempt at the genre of comedy-about-love, but in my guts I feel how inappropriate would it be to call it a “romantic comedy” – Fallen Leaves actually seems to me closer to the theather of the absurd. Its humour is sinister, bittersweet; for me it tastes much more closer to the “mood” of Ionesco, Beckett or Harold Pinter than to Woody Allen or Chaplin.

To watch it inside one of Amsterdam’s greatest places for the gathering of cinephiles, together with some 40 people in a very cold and chilly dutch afternoon, could Furnish me with some knowledge of social reaction to the film that is unaccessible to anyone who has seen it alone, on a private screen. It’s sad, I guess, that most of people’s cinematic experiences nowadays are deeply impoverished by the fact that the film is watched in aloness, in private space, with no shared aesthetic experience in the dark conviviality and co-presence that the movie theather provides.

This film rewards us, in a public screening, with the strange spectacle of laughter from the audience in certain moments: for instance, some laughs when he invites her to drink coffee and, while she’s busy requesting food at the cafeteria, he quickly drops alcohol in his drink. She witnesses that – she knows right from the start, from the first date, he’s a drunk.

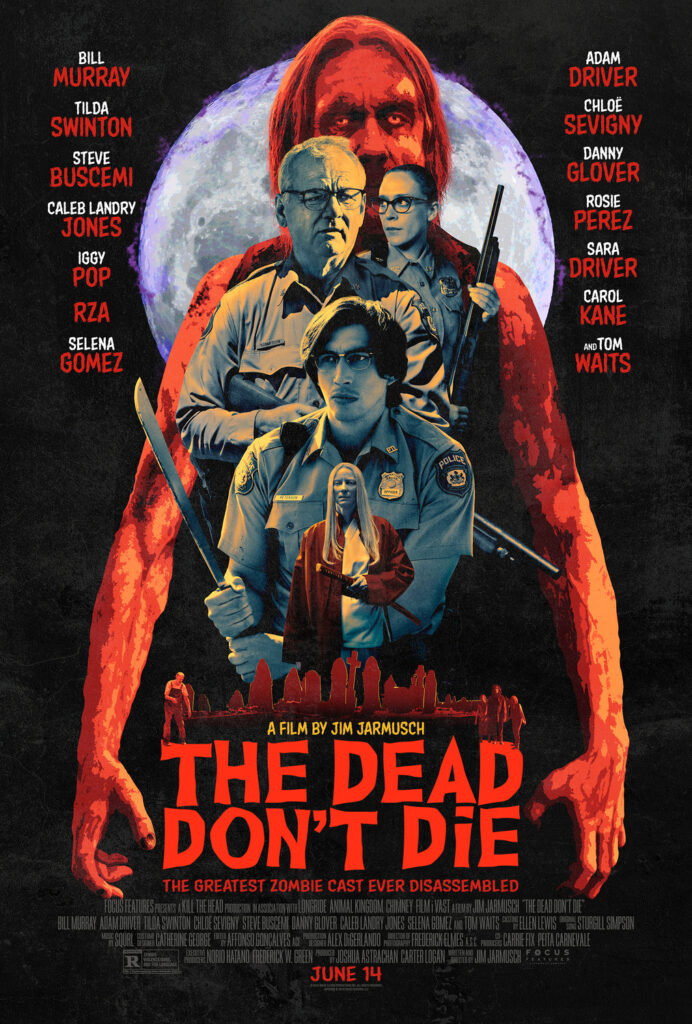

Perhaps he mixes alcohol and caffeine to gather up the courage to ask the cute blondie on a date. He asks her to a cinematic rendezvous, and his choice of film is very un-romantic. More laughs from the audience when he takes the girl to see a zombie movie, ultraviolent, with policemen slaughtering pittillesly the degraded, zombiefied ex-humans. Here, Kaurismaki quotes Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die and also deepens his underlying comment about the absurdities of contemporary, zombified life.

As if separated by an invisible wall, he and she are filmed inside the cinema with bodies both side-by-side but yet locked in immobility and un-touchability. More laughs from the audience when they’ve left the cinema and she remarks: “the police didn’t have a chance, they were far too many zombies.” The camera had just shown her dead-serious face while watching the film’s carnage, but she says to him: “I’ve never laughed so much in my life” – she is either lying or she’s being ironic. I stand for the irony hypothesis.

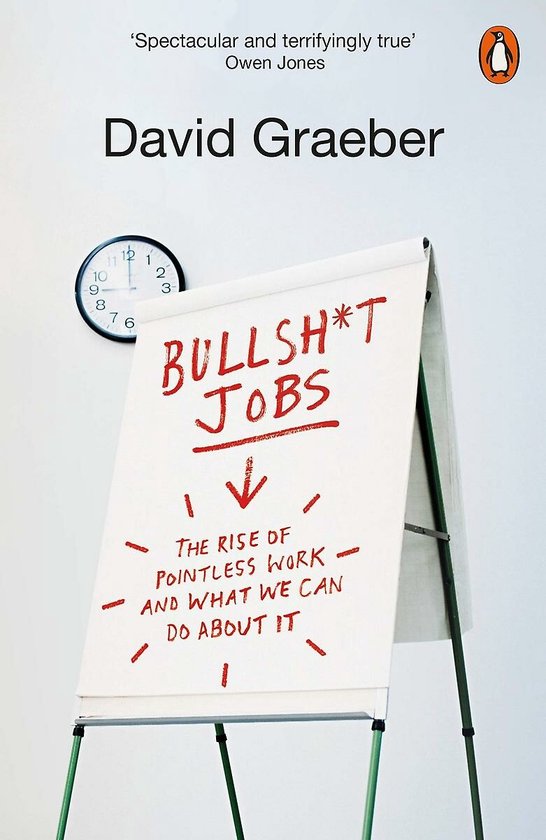

The scene is depicted in the film’s poster, where a lovely dog is also shown in the back. The man looks at her while she gazes at the movie flick, and perhaps he’s thinking to himself: did I screw up this fuckin’ date by choosing an ultraviolent film instead of something lighter and funnier? Yet, we feel like he can’t help but choose aesthetically something that relates to his own life as a blue-collar worker trapped in bullshit jobs and always getting fired because of his relentless alcoholism. We also discover that the girl actually enjoyed herself in the zombie film’s brutalism but she herself is also locked in bullshit jobs (the film starts with her working at the supermarket, registering the bar codes for several dozens of animals corpses – I mean packed meat – that a costumer is purchasing).

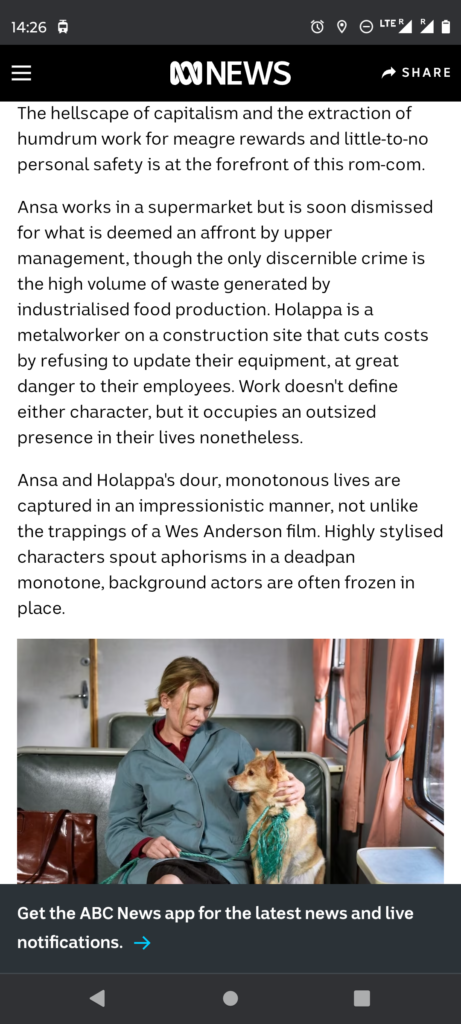

For those interested in sociology, the film offers several glimpses into what David Graeber called bullshit jobs: it’s heartbreaking and revolting to watch her being fired from the supermarket she works in because she hides in her purse and tries to take home some food destined to the trash can. Instead of throwing away food after the “use by” date has expired, she decides to appropriate it, a scene that hints at her hunger and malnutrition: she will eat some food that is perhaps unfit for consumption and may damage her health. The scene also shows a glimmer of hope in the solidarity she receives from colleagues, but the realm of the bosses is shown as merciless – she’ll soon start another bullshit job at the Buenos Aires café, cleaning glasses with remnants of beer in it, in an environment where human communication seems to have been frozen into very low degrees of meaningful interaction.

One apex of bitter irony in the film happens after the screening of The Dead Don’t Die: the guy seems to have been blessed with luck, the girl kisses him in the cheek and gives him her number, signaling that a next date can be perhaps arranged. But the paper with her phone number is blown away by the wind when he reached for yet another cigar – he’s a freakin’ chimney and his colleague of work has warned him: you might catch your death by smoking that much. It’s hard to call this bad luck – it seems that his conduct is deeply rooted in addiction to nicotine and alcohol, and the piece of paper gets blown away not because the cosmos is against him, or because a punishing god is teaching him a lesson, but as a result of his own inability to resist his compulsive behavior. He then drinks his away into losing 2 jobs – and to almost losing the girl.

When, after the zombie flick, they said goodbye, he didn’t yet know her name. She promised to tell him on a next date – she clearly hints at “call me, let’s meet again”, but he never will. He lost the damn number. But it’s still a small town, with only one movie theather, and they manage to schedule a second date, this time at her apartment. He treats it like a pub and shows off once again his alcoholism. She kicks his ass outta her life, saying that both her father and brother died because of alcohol addiction, and that her mother has died of grief. Neither the girl nor the boss will take him, accept him or love him as a drunkard.

Fallen Leaves is the chronicle of a downward spiral. He goes to the bottom of the well, he drinks self-destructively, he seems gripped by the iron claw of nihilism. It reminded me of Billy Wilders Lost Weekend. Kaurismaki depicts a sad addiction, a vicious circle, and the firm resolution he finally undertakes to sober up (his effort to “wise up”) ends up leading to an also very disappointing outcome. He promises to her that drinking is over and done – he’s show emptying his bottles at the bathroom sink. He promises that from now on he’ll be sober, a practioner of temperance. She allows him to come for a third date – they haven’t yet kissed.

But his wonderful plan to be a better person gets suddenly interrupted by the train that strikes him into a coma. Just when you think you’ve made a resolution that will get your life back on track after it has gone astray, the world surprises you with a train that runs over all your beautiful plans. But Fallen Leaves is not a punch in the gut: it leaves a door open for the possibility of better times. Kaurismaki doesn’t kill the guy and he doesn’t make the girl give up on him.

He’ll leave the hospital crippled but livened because the girl went to nurse him, went to convoke him back to living. More laughs from the audience, including from myself, when she goes to the hospital while he’s unconscious and tries to pull him out of his coma by pretending to share breaking news, including one about Finland winning the soccer World Cup against Brazil. She has now adopted a lovely dog named Chaplin, and with canine companionship she has been trying to cure her terrible long standing existential solitude.

Love is not holy, not inerrant, not delightful – in Kaurismaki’s aesthetics of the absurd love is a profane mess, a longing by lonely humans who feel devoid of affection and meaning in lives that the capitalist market-culture renders into a desert of bullshit jobs, unsatisfying consumerism and day-to-day brutalism in relationships.

For me, this existencial solitude has a very significant symbol in the new plate and new knifes and forks she rushes to buy when she’s about to receive him for dinner. She’s so lonesome that her house has only one plate – her own. When she gets disappointed about him – fucking drunk! Using my apartment as his pub! – she throws the extra plate in the garbage can. She’d rather have a relationship with a dog. She jokes with her friend we shouldn’t compare men with pigs – it’s very disrespectful with the lovely creatures that pigs are.

The absurd leaks through the cracks of these imperfect relationships in ways which also made me recall Kundera‘s wonderful book “Laughable Loves” (1967). He’s also very lonely, existentially bleak, and this leads him to dreams of love as a redemptive force that send him straight into the arms of delirious reasoning. At the pub, he’s telling his friend, after having only met the girl once (for the zombie flick) – “we almost got married!” – but a few seconds afterwards he’s obliged to confess -“I don’t even know her name”. The film ends and the only bodily contact between the man and the woman that could be said to be significantly erotic is the kiss on the cheek she bestows upon him – afterwards, he raises his hand to his kissed cheek in a mysterious way, as if he was going through some epiphany, some rare experience.

Propelled also by an excellent soundtrack, Kaurismaki’s absurd tale of imperfect loving also deals with how geopolitics finds a way to mess with our psyches. The war in Ukraine rages on; the film features several news about the Russian military operations during the last few years (actually, the Russo-Ukrainian war can be said to be raging for 10 years, from 2014 until 2024). She can’t help but hear the blastful news on the radio; but it depresses her, so she quickly flips the dial and puts on some music. It’s mainly finnish romantic pop, melodramatic and escapist.

Life’s already too bleak and lonely, she can’t stand to make it worse by listening in to lots of war reporting. Sometimes the characters find some to fun at the karaoke bar – it’s actually where the protagonists meet, even tough neither she or he sing at the occasion. Locked in vicious circles, the couple does not succed to arrive not even to the common result of a happy-ending leaning film: the redeeming kiss. Their mouths never kiss on screen.

The finale has nothing of grandeur, it’s not a dissolution of absurdity. And yet it’s an adorable ending for a film that ends up feeling lovely and delicate. He wakes up from his coma, alive after his near-death-experience after being run over by the train. He’s crippled, traumatized, probably still addicted to cigars, alcoholo and a romantic phantasy that has already received several bruises and blows. While he follows her (and Chaplin, the dog), walking through the field of fallen leaves, some more optimistically minded might read this a happy ending of sorts. They are walking together, the three of them, an inter-species micro-comunity, with their scars and broken bones, finally having reached some sort of imperfect togetherness.

Yes, but my pessimistic stance leads me to another conclusion. This tragicomedy is autumnal, bittersweet. This film is not similar to the conducts of a cheerleader. Human frailty is all around. I read the last scene as something else than love’s victory: the girl, perhaps, went to the hospital not because she loves him sincerely, but out of pity and also because she feels some guilty – this wouldn’t have happened if he hadn’t been invited to the house. The fact that the man was on his way to her flat, after making promises of being a better man from now onwards, and the fact the accident happened in his journey towards her, gets her into a situation where she feels responsible. But pity is a bad foundation for love – some might say it isn’t love at all.

He’ll probably face, after hospitalization, a very difficult recovery process. Jobless, with broken bones, with his body filled with pain, with his habilities to move severely impaired, it’s quite possible that he would become too much of a burden upon her. Perhaps she last scene shows not the victory of love, but a woman who’ll prefer to live with her dog than to merry a broken-down fucked-up penniless man who’ll probably drown his sorrows in whisky once again.

Once again, the optimist may read the last scene as “spring is coming” after the autumn, the trees of life will regain their leafs, fruits will blossom forth in the beautiful future of this couple. But I would object, in a more pessimistic perspective, that nothing in the previous trajectories of this lifes leads us to conclude that what’s coming is the consumation of love’s redeeming powers instead of the continuation of love’s profane, hurtful, difficult, chaotic mess.

For sure, humour sheds some redeeming light upon these dark materials. Music also infuses life into deadening situations – and here “Les Feuilles Mortes”, by Jacques Prévert and Joseph Kosma, seems to set the mood for the whole film. Leading performances by Alma Poysti and Jussi Vatanen are both excellent and very authentic – the difficult task that the actors managed to convey here is the distance between bodies, the abyss between hearts, and the precarious attempts to build bridges that seem to be always collapsing.

Kaurismaki’s film is drenched in a context of bloody war, bullshit jobs and way-too-many-zombies. This is not about love’s triumph, but rather a slice-of-life cinematic masterpiece that shows lives struggling to find love and companionship in an imperfect, errant, tortuous, absurd-filled journey which bears the mark of sempiternal incompletion.

Eduardo Carli de Moraes

Amsterdam, January 2024

READ MORE: Senses of Cinema

Sérgio Moriconi and Carlos Alberto Mattos – Scream and Yell (in portuguese).

ABC – https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-02-14/fallen-leaves-review-aki-kaurismaeki-movie-oscar-nominee/103458766

SPREAD YOUR LOVE LIKE A FEVER: Facebook – Instagram – X (Twitter).

The aesthetics of the absurd and love’s profane mess in Kaurismaki’s “Fallen Leaves” (2023): https://t.co/fsVTfGHiL3

— A Casa de Vidro (@acasadevidro) January 24, 2024

HOW TO WATCH THIS FILM: Download via Torrent (5.6 GB) – Subtitles in Brazilian Portuguese.

Publicado em: 24/01/24

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes

Carlos Alberto Mattos

Comentou em 14/02/24