Capitalismo à la Pinochet: O neoliberalismo latino-americano segundo Naomi Klein em “A Doutrina do Choque”

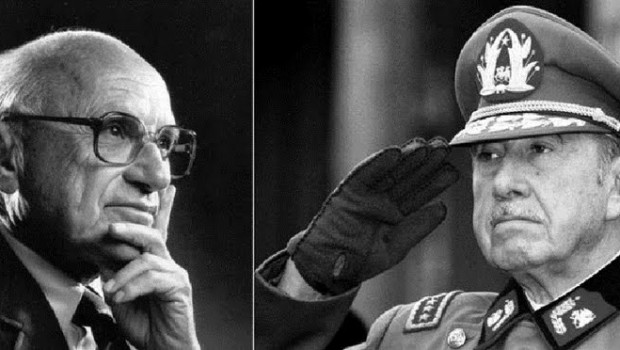

Um dos “heróis” mais celebrados por aqueles que defendem o capitalismo neoliberal, ou seja, uma economia de “free market” sem nenhuma regulação social ou estatal, é o economista Milton Friedman, figura que teve tenebrosas conexões com a ditadura militar de Augusto Pinochet no Chile.

Após o golpe violento de 11 de Setembro de 1973, que derrubou o governo democraticamente eleito de Salvador Allende, o conluio entre as elites financeiras dos EUA e o novo regime ditatorial de Pinochet pôs em ação aquilo que Naomi Klein chamou de “A Doutrina do Choque”. Os “Chicago Boys”, gangue liderada por Friedman e seus comparsas, só pôde impor a “liberalização dos mercados” utilizando-se simultaneamente da proliferação de atrocidades contra todos os cidadãos chilenos que se opunham ao novo regime de ultra-capitalismo que foi imposto de modo autoritário após o assassinato de Allende. A tal da “liberdade dos mercados” andou pari passu com a tortura de 100.000 a 150.000 pessoas, além do assassinato sistemático de opositores do regime (entre eles, o cantor folk Victor Jara e o genial poeta Pablo Neruda).

Em outros cantos da América Latina, ditaduras militares semelhantes também impuseram a abertura dos mercados aos capitais estrangeiros e as portas escancaradas para a chegada das mega-corporações trans-nacionais. Sob a mão férrea dos tiranos de fardas, o Brasil e a Argentina também vivenciaram a truculência da aliança entre a barbárie militarizada e a doutrina econômica neoliberal de Friedman e seus comparsas.

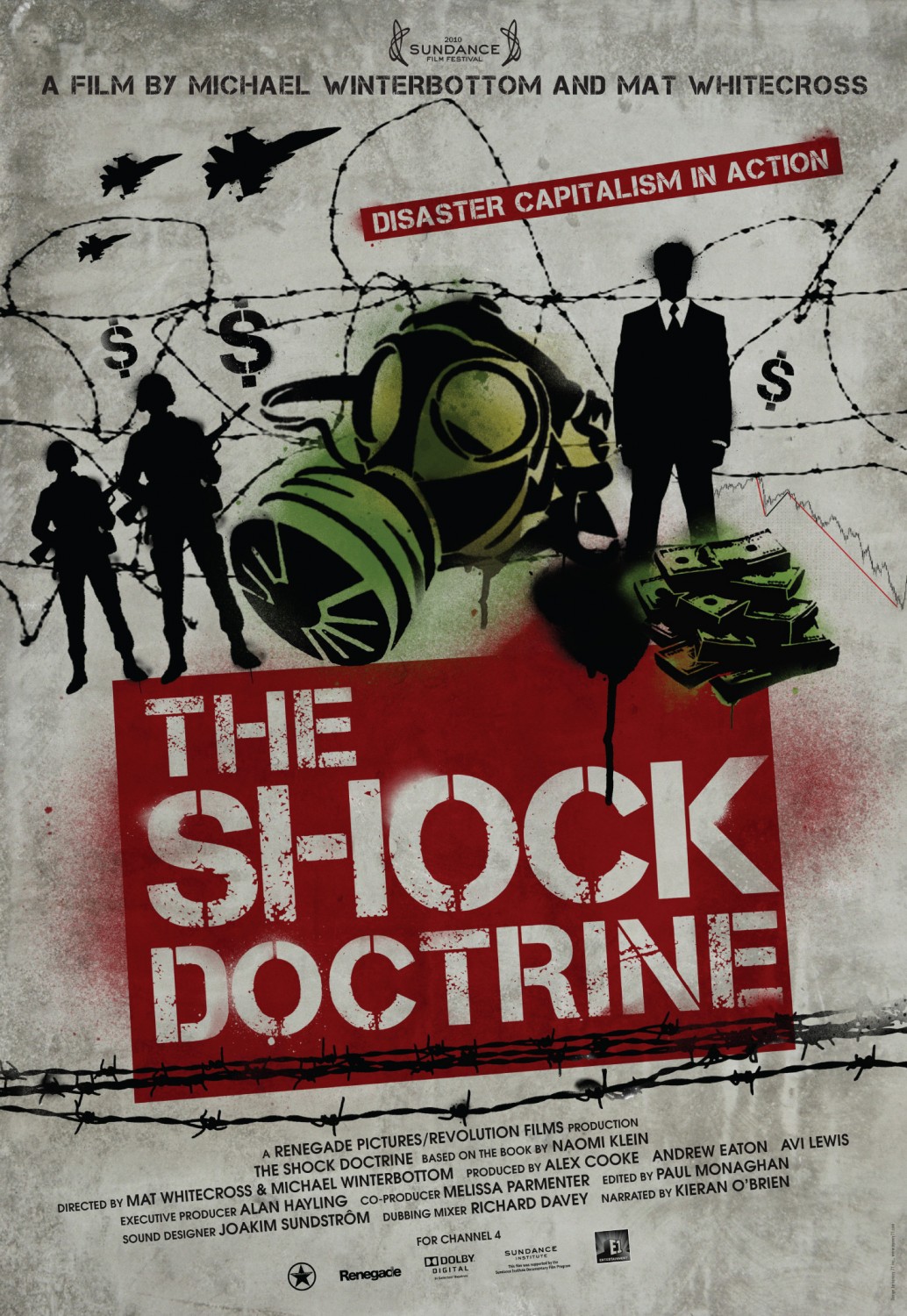

Em um dos livros políticos mais importantes deste século, Naomi Klein expôs claramente esta ainda reprimida verdade histórica sobre o nosso continente: por aqui, o capitalismo neoliberal não chegou após ser escolhido nas urnas pela vontade soberana do povo, mas foi imposto pelos tanques e soldados de ditaduras militares entreguistas, apoiadas ideológica e financeiramente pelos tubarões de Washington e Wall Street. É que a famosa “mão invisível” de Adam Smith jamais pode funcionar sem o truculento punho, muito visível e ameaçador, de um complexo militar-policial-carcerário que foi tão brilhantemente criticado por Foucault e Angela Davis. A “liberdade econômica” pregada pelos neoliberais não passa, assim, de uma farsa sangrenta diante da pilha de cadáveres e dos gritos infindáveis dos torturados e exilados que o “free market” pôs como preço para seu triunfo.

LEIA TAMBÉM: NAOMI KLEIN, “MILTON FRIEDMAN NÃO SALVOU O CHILE”: “Depois do golpe e da morte de Allende, Pinochet e os Chicago Boys fizeram de tudo para desmantelar a esfera pública do Chile , leiloando empresas estatais e cortando as regulações financeiras e comerciais. Foram criadas enormes fortunas neste período de tempo a um custo terrível…”

Cito um trecho crucial de “The Shock Doctrine“:

“Milton Friedman first learned how to exploit a large-scale shock or crisis in the midseventies, when he acted as adviser to the Chilean dictator, General Augusto Pinochet. Not only were Chileans in a state of shock following Pinochet’s violent coup, but the country was also traumatized by severe hyperinflation. Friedman advised Pinochet to impose a rapid-fire transformation of the economy—tax cuts, free trade, privatized services, cuts to social spending and deregulation. Eventually, Chileans even saw their public schools replaced with voucher-funded private ones.

“Milton Friedman first learned how to exploit a large-scale shock or crisis in the midseventies, when he acted as adviser to the Chilean dictator, General Augusto Pinochet. Not only were Chileans in a state of shock following Pinochet’s violent coup, but the country was also traumatized by severe hyperinflation. Friedman advised Pinochet to impose a rapid-fire transformation of the economy—tax cuts, free trade, privatized services, cuts to social spending and deregulation. Eventually, Chileans even saw their public schools replaced with voucher-funded private ones.

It was the most extreme capitalist make over ever attempted anywhere, and it became known as a “Chicago School” revolution, since so many of Pinochet’s economists had studied under Friedman at the University of Chicago. Friedman predicted that the speed, suddenness and scope of the economic shifts would provoke psychological reactions in the public that “facilitate the adjustment.” He coined a phrase for this painful tactic: economic “shock treatment.”

In the decades since, whenever governments have imposed sweeping free-market programs, the shock treatment, or “shock therapy,” has been the method of choice. Pinochet also facilitated the adjustment with his own shock treatments; these were performed in the regime’s many torture cells, inflicted on the writhing bodies of those deemed most likely to stand in the way of the capitalist transformation. Many in Latin America saw a direct connection between the economic shocks that impoverished millions and the epidemic of torture that punished hundreds of thousands of people who believed in a different kind of society.

As the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano asked, “How can this inequality be maintained if not through jolts of electric shock?” Exactly thirty years after these three distinct forms of shock descended on Chile, the formula reemerged, with far greater violence, in Iraq…

Since the fall of Communism, free markets and free people have been packaged as a single ideology that claims to be humanity’s best and only defense against repeating a history filled with mass graves, killing fields and torture chambers. Yet in the Southern Cone, the first place where the contemporary religion of unfettered free markets escaped from the basement workshops of the University of Chicago and was applied in the real world, it did not bring democracy; it was predicated on the overthrow of democracy in country after country. And it did not bring peace but required the systematic murder of tens of thousands and the torture of between 100,000 and 150,000 people.

Salvador Allende, as he watched the tanks roll in to lay siege to the presidential palace, had made one final radio address suffused with this same defiance: “I am certain that the seed we planted in the worthy consciousness of thousands and thousands of Chileans cannot be definitively uprooted,” he said, his last public words. “They have the strength; they can subjugate us, but they cannot halt social processes by either crime or force. History is ours, and the people make it.”

The seed that Allende referred to wasn’t a single idea or even a group of political parties and trade unions. By the sixties and early seventies in Latin America, the left was the dominant mass culture — it was the poetry of Pablo Neruda, the folk music of Victor Jara and Mercedes Sosa, the liberation theology of the Third World Priests, the emancipatory theater of Augusto Boal, the radical pedagogy of Paulo Freire, the revolutionary journalism of Eduardo Galeano and Rodolfo Walsh. It was legendary heroes and martyrs of past and recent history from José Gervasio Artigas to Simon Bolivar to Che Guevara.

In Santiago, the legendary left-wing folk singer Victor Jara was among those taken to the Chile Stadium. His treatment was the embodiment of the furious determination to silence a culture. First the soldiers broke both his hands so he could not play the guitar, then they shot him forty-four times, according to Chile’s truth and reconciliation commission. To make sure he could not inspire from beyond the grave, the regime ordered his master recordings destroyed. Mercedes Sosa, a fellow musician, was forced into exile from Argentina, the revolutionary dramatist Augusto Boal was tortured and exiled from Brazil, Eduardo Galeano was driven from Uruguay and Walsh was murdered in the streets of Buenos Aires. A culture was being deliberately exterminated.

In Chile, Pinochet was determined to break his people’s habit of taking to the streets. The tiniest gatherings were dispersed with water cannons, Pinochet’s favorite crowd-control weapon. The junta had hundreds of them, small enough to drive onto sidewalks and douse cliques of school children handing out leaflets; even funeral processions, when the mourning got too rowdy, were brutally repressed.

In Brazil, the junta did not begin mass repression until the late sixties, but there was one exception: as soon as the coup was launched, soldiers rounded up the leadership of trade unions active in the factories and on the large ranches. According to “Brasil: Nunca Mais (Never Again)”, they were sent to jail, where many faced torture, “for the simple reason that they were inspired by a political philosophy opposed by the authorities.” This truth commission report, based on the military’s own court records, notes that the General Workers Command (CGT), the main coalition of trade unions, appears in the junta’s court proceedings “as an omnipresent demon to be exorcised.” The report bluntly concludes that the reason “the authorities who took over in 1964 were especially careful to ‘clean out’ this sector” is that they “feared the spread of. . . resistance from the labor unions to their economic programs, which were based on tightening salaries and denationalizing the economy.”

Some of the most infamous human rights violations of this era, which have tended to be viewed as sadistic acts carried out by antidemocratic regimes, were in fact either committed with the deliberate intent of terrorizing the public or actively harnessed to prepare the ground for the introduction of radical free-market “reforms.” In Argentina in the seventies, the junta’s “disappearance” of thirty thousand people, most of them leftist activists, was integral to the imposition of the country’s Chicago School policies, just as terror had been a partner for the same kind of economic metamorphosis in Chile.”

– NAOMI KLEIN.

The Shock Doctrine: The Rise Of Disaster Capitalism.

[youtube id=http://youtu.be/aSF0e6oO_tw]

Publicado em: 31/01/16

De autoria: casadevidro247

marielfernandes

Comentou em 25/10/14