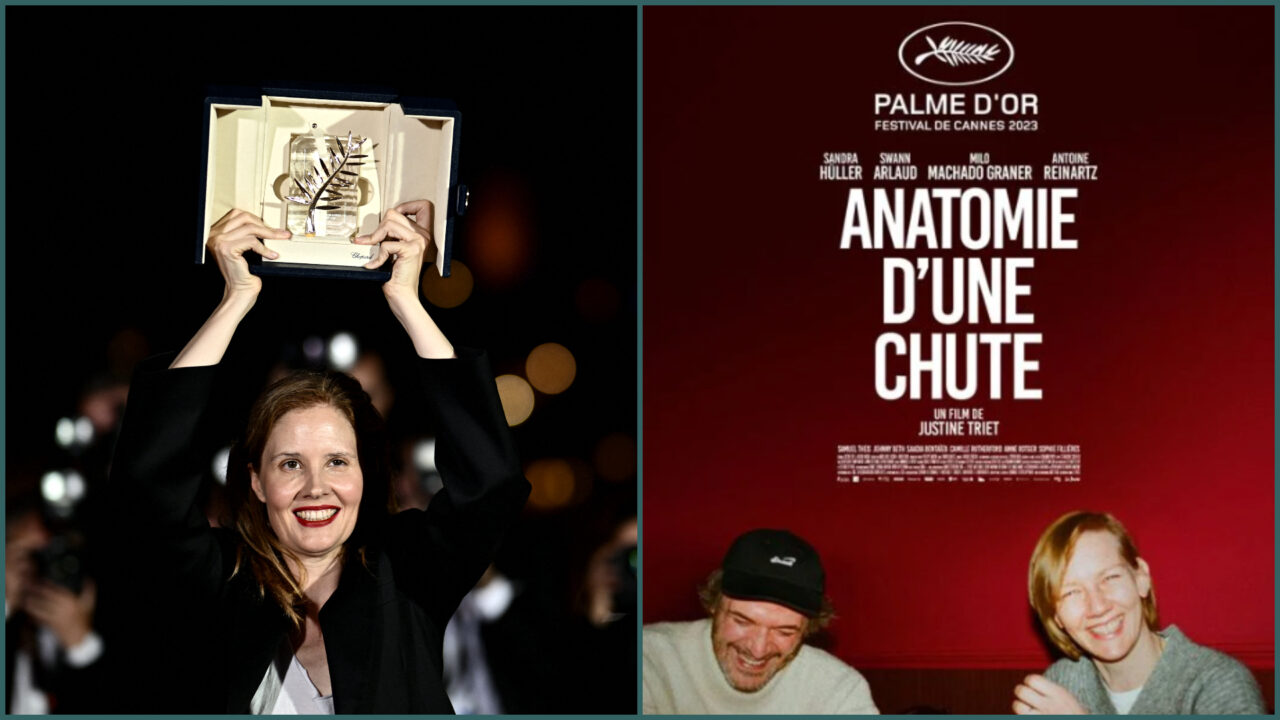

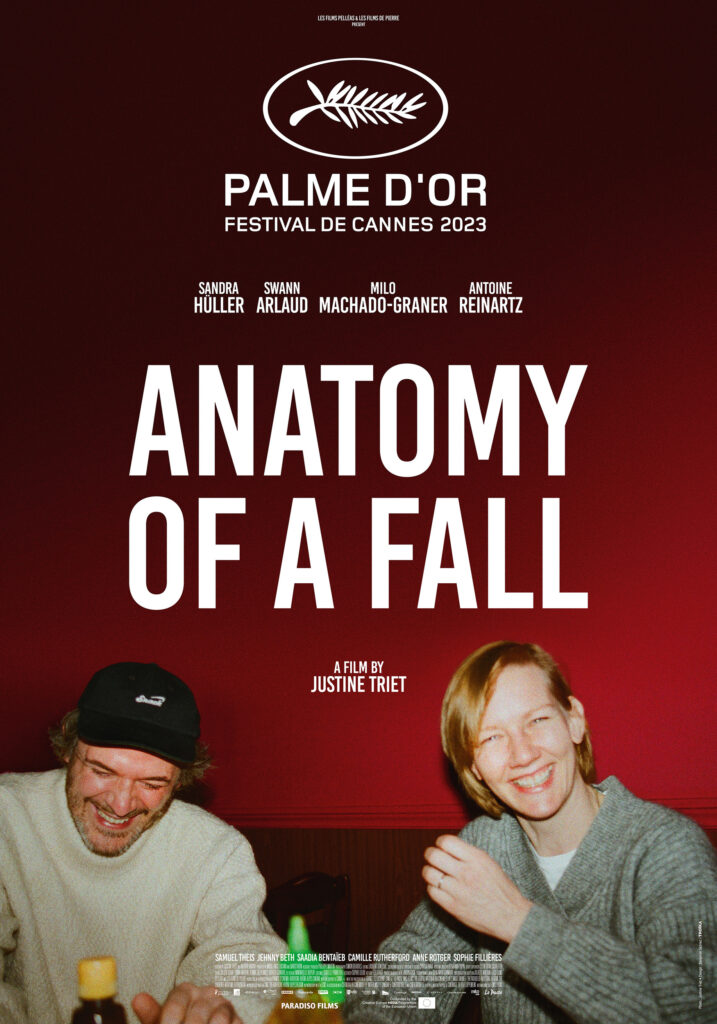

The male gaze falls from grace: concerning “Anatomy of a Fall” (Justine Triet), winner of the Cannes Palm D’Or

A film should be judged not only by the aesthetic and intellectual experience it provides during the screening, but also by its resonance afterwards: does it evanesce quickly from memory, or does it linger on the mind, continuing to stimulate it? This seems to entail that a film critic shouldn’t rush to publish a text after he has seen the movie, but should sleep on it, so to speak, and wait for the experience to settle in, digesting it and considering its resonating effects for a few days.

Perhaps the most noteworthy virtue of Justine Triet‘s thought-provoking <Anatomie D’un Chute> – <winner of the 2023’s Palm D’Or in Cannes> – lies in an intriguing <ambiguity> that the artist refuses to solve. The film ends without resolving all the riddles it has proposed. It doesn’t dispel the doubts it provokes. It estimulates discussions at the café or the pub afterwards, where different perspectives may be upheld, concerning essentially this crossroads of alternatives: did the woman actually kill her husband, or did he commit suicide?

It’s an artistic technique of putting an end to an artwork without really ending it – as if the film chooses for its final phrase not a “.” or a “!” but a “…” or a “?” – in other words, Triet has the delicacy and artistic dexterity to arrive at the end of a long journey (the playing time is 150 minutes) providing us with reasons for reticence, doubting and questioning. The spectator is then called upon the task of continuing the anatomy of this mysterious fall.

It’s also an aesthetic choice of political significance because it’s much more “democratic” – in the sense of allowing public discussion and inviting the spectator’s opinion about the matter – when you deliver a somewhat open-ended narrative than it would be if a resolution was imposed upon the viewers in a manner we could deem “authoritarian” (this is what happened, no discussions allowed!).

SPOILER ALERT

Of course the narrative leads to a sort of conclusion: when the trial is over, our protagonist Sandra Voyter (brilliantly played by Sandra Hüller) is set free. The jury didn’t find her guilty of the murder of her husband. Which means that the hypothesis of the man’s suicide won the stuggle of main hypotheses explaining the death of teacher and wanna-be-writer Samuel Theis. But we are left to ponder: what if the child of the couple has made a decision to testify in such a manner as to save his mommy from prison? What if we are dealing here with something similar to Pascal’s argument about God: the child, even tough he’s doubtful, jumps to the decision that his heart desires and, through wishful thinking, embraces the thesis that his mother is inoccent of murder?

Psychology-wise, it makes a lot of sense that a vulnerable, almost blinded and severely traumatized 11-year-old kid might choose to convince the court that his father commited suicide, even tough we doesn’t deem impossible that his mother actually stroke the fatal blow to the head of his father. A recording from the day that preceded Samuel’s death surfaced on the trial and it was only then that the son could really witness (through sound) how violent and vicious the altercations of his parents could get. The REC also shows that verbal exchange of accusations and insults could in fact escalate to physical violence, broken wine glasses, slaps in the face and bone-breaking punches against the wall.

The remembrance of an episode concerning the dog Snoop (winner of a Prize for animal acting in Cannes!), which supposedly ate Samuel’s vomit after a suicide attempt, tends to construe the father’s personality as prone to self-destruction. But there’s no absolute truth here, the filmmaker leaves at least a fringe of the Door of Doubt open to us: yes, it’s possible she killed him in a sudden rage after he played on loop some annoyingly loud music on his mega-speakers while she was trying to concede an interview to an interesting, beautiful literature researcher.

Another very intriguing matter here is self-fiction. The plot makes clear that Sandra is a sucessfull writer, with several books published, and that she draws from her own life experiences to write her novels – beggining with one about the death of her mother. She’s also quoted on TV as saying she tries to invent some much upon this basic experience-grounded inspiration so as to make fiction kind of surpass biography. Henry Miller also did this. The husband, in contrast, seems to continuously fail at his own attempt to write novels. He perhaps feels overshadowed by her wife’s accomplishments. He abandons his novels halfway – and the good ideas he could actually get written down, he can’t lead to a finished and publishable work.

The film, then, deals with gender and sexuality in quite an interesting way. We’re aware that in societies ruled by “the patriarchs”, usually women are overburden with domestic and child-bearing labour. Usually, it’s “the second sex” the one who is justly denouncing a lack of time to engage in meaningful activities concerning, for example, artistic expression and intellectual endeavours. Here, this gender archetype is twisted and turned head over heels. It’s the man who feels he is being robbed of his time. It’s the man who feels frustrated, hurt in his pride because he feels as an underachiever in the field of literature.

The film also deals inteligently with the matters concerning trauma and resentment: when he was 4, the kid got involved in an accident – run over by a motorcycle, optic nerve permanently damaged, on a day that his father was responsible to pick him up at school and failed to do so. Samuel is portrayed as someone tormented by fatherly guilt about this episode – and Sandra admits to court she resented him, and held him responsable, for the traumatizing event. This leads to the reasonabilty of the suicide thesis: he had a tremendous load of guilt in his psyche, he had tried to kill himself sometimes previously, he was a “project man” unable to carry his works-in-progress to conclusion etc.

The jury took its decision after hearing the kid’s tale: he and his daddy were driving to the vet with a sick dog, and daddy talks about the death of animals: prepare yourself, my son, it will certainly help, the deaath of creatures you love is unavoidable, you will have to learn to live without him etc. The kid, in court, interprets this as follows: daddy wasn’t talking about the dog but about himself. The hypothesis of suicide gains ground and wins the battle. A tale told by a kid is taken in as evidence. A jury is convinced also by emotion and not by logic only. But it doesn’t rule out as completely preposterous the opposite hypothesis.

This would be a very strange choice of suicide method, indeed: the window from which Samuel supposedly jumped was not that high and any rational human being, even one that is deranged by suicidal ideations, would ask himself: it this fall enough to kill me, or will it only screw me up pretty badly? Will I die or will I only jump to a worse life, with much more physical suffering due to broken bones and probably the constraints in movement of a paraplegic?

Jumping from that window would amost certainly fail to cause a death. It’s strange this is not brought up by the prosecutor on court – and it seems to be a small flaw of the script. If Samuel wanted to kill himself, wouldn’t he chose some more appropriate method? Is the plot suggesting that we had already tried and failed with the aspirines, and this explains why he decided to shift to another self-extinction method? Or are we to judge he wanted to make a statement through a theatrical act of almost-suicide, in the “cry for help” sort, aiming to get himself severely bruised?

The matter of bisexuality is also brought on here: Sandra admits, during the trial, that she had extra-marital affairs with other women. She admits that the relationship with her husband, especially after the incident that almost blinded their son, did put Eros in crisis. She admits she was sincere about her affairs for a while, but then began concealing them. In the day that preceded the fatal fall, the husband explodes in resentment, posing as a victim, as a husband who has been cheated upon and robbed of his time. But she stands her ground, defends her decisions, and in this film lesbofobia doesn’t dare to rear its ugly head that much, despite the prosecutor’s attempt to paint her as a mischevous traitor that made her husband terribly hurt and jealous.

The point of the film also seems to be this: this woman is not only judged as a murder-suspect, but all her actions as a sexual agent, as a writer, as a mother, are under judgement as well. The film deals with intimacy being brought to public scrutiny. It offers us acess to all the chaos and contradiction of a marriage – one might recall here some masterworks by Bergman, Woody Allen or John Cassavettes – and leaves us with lots of food for thought. When it ends, with scenes of bodily intimacy and comforting caresses between lawyer and client, and then mother and child, and then woman and dog, it also highlights the emotionality of the human condition, inextricable from the processes of Law when it deals with the so-called “crimes of passion”.

Male dominance of film production is an historical fact that we’re only beggining to confront, and this is another welcome phenomenon that comes along with Anatomy of a Fall’s resounding secular consecration. This is the 3rd time in its history spanning 76 editions that a Palm D’Or is prized upon a woman – prior to Justine Triet (which received the golden honour from Jane Fonda’s hands and discoursed against Macron’s govt repression of recent protests in France), only Julia Ducorneau (“Titane”, 2021) and Jane Campion (“The Piano”, 1993) had managed the feat. The jury was presided by Ruben Ostlund, 2-times winner of the Palm D’Or.

A similar case could be made about the <USA’s Academy Awards: it began delivering its awards in 1929> and woman-winners of Best Director can be quickly listed: K. Bigelow (The Hurt Locker), Chloé Zhao (Nomadland) and Campion (Power of the Dog), all of them from 2010 onwards.

Those are symptoms of the still on-going hegemony of “the patriarchs” (cleverly denounced in Angela Saini’s books) in the field of filmmaking. Anatomy of a Fall reveals the cracks in masculinity all around its very well-construed plot and offers us a career-defining performance by Sandra Hüller as a very complex and bruised woman, doing the best she can to sail through the tempest of chaotic relantionships and the onslaughts of contingent tragedies.

Written by Triet and Arthur Harari, the film also features not-to-be-forgotten performances of a kid and a dog, which also adds up to de-center the adult male from his long-held position as protagonist. Vulnerability, here, gets more evenly distributed. And a huge shadow of doubt looms over the film like a gray poetic cloud that bathes this work-of-art in a strange light that adds to its continued resonance.

A point could also be made that films directed by women such as Triet, Courneau, Despentes and Sciamma (to mention only the frenchies) have been busy in de-constructing masculinity and trying to brush it away to the margins – so other themes can come to the foreground, other relations can be protagonists, thus queering up the screen. It will take indeed much more artworks, efforst and cultural renovation for the male gaze to finally fall from his long held pedestal.

Eduardo Carli de Moraes

Amsterdam, October 19th 2023

Seen at the Rialto / De Pijp

Permanent Link: https://acasadevidro.com/anatomyofafall/

The male gaze falls from grace: concerning “Anatomy of a Fall” (Justine Triet), winner of the @cannes Palm D’Or 2023: Read it @acasadevidro – https://t.co/9vTYt9zHVU pic.twitter.com/KpAxGEATya

— A Casa de Vidro (@acasadevidro) October 19, 2023

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: The Guardian – IMDB.

Publicado em: 19/10/23

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes