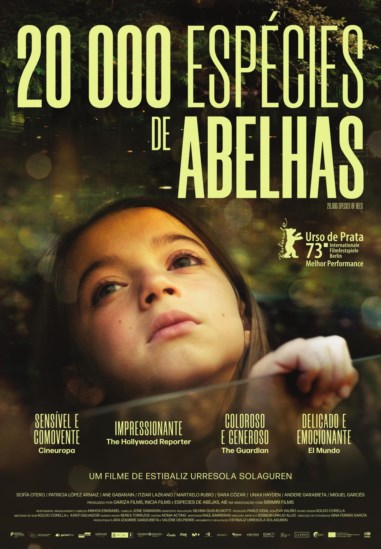

“20.000 Species of Bees”, a new masterpiece of Queer Cinema, invites us to see gender fluidity through the wise lens of cariño

<20.000 SPECIES OF BEES> (2023) is a masterpiece of Queer Cinema. This statement can be misunderstood as an affirmation of the value or merit of this compelling film only within a certain niche or genre. That’s not my aim: instead of locking it inside the box of queer films, I would like to suggest that cinema as a whole has been enriched enormously in the last decades by so-called queer films.

What the text that here begins will attempt to vindicate is queerness in cinema as one of the greatest artistic and aesthetics developments in the recent history of the 7th art. In simpler words: 20.000 species of bees is a masterpiece of cinema. And it happens to be an artwork than can be categorized within the <New Queer Cinema> trend, which had many recent additions to its gallery of masterful works: <Orlando – My Political Biography, by Paul Beatriz Preciado>; <The Miseducation of Cameron Post, by Desirée Akhavan>, <Kokomo City by D. Smith>, and <Closet Monster by Stephen Dunn> being a few of the greatest that rush to memory.

Without ever pronouncing the words “transexuality” or “gender fluidity”, 20.000 Species of Bees offers us more than a queer tale with very young protagonist. It teaches wisdom; it sheds a light to a path of cariño, an overcoming of the hatefulness and violence connected with homophobia and male supremacy’s values and conducts. It’s the debut feature film by <Basque filmmaker Estibaliz Urresola Solaguren>, born in 1984, whose style can be called neo-realist or naturalistic, evoking comparisons to the Dardenne brothers, Ken Loach, Gus Van Sant, Mike Leigh etc. – even tough the director herself recognizes also a strong influence by the argentinian Lucrecia Martel.

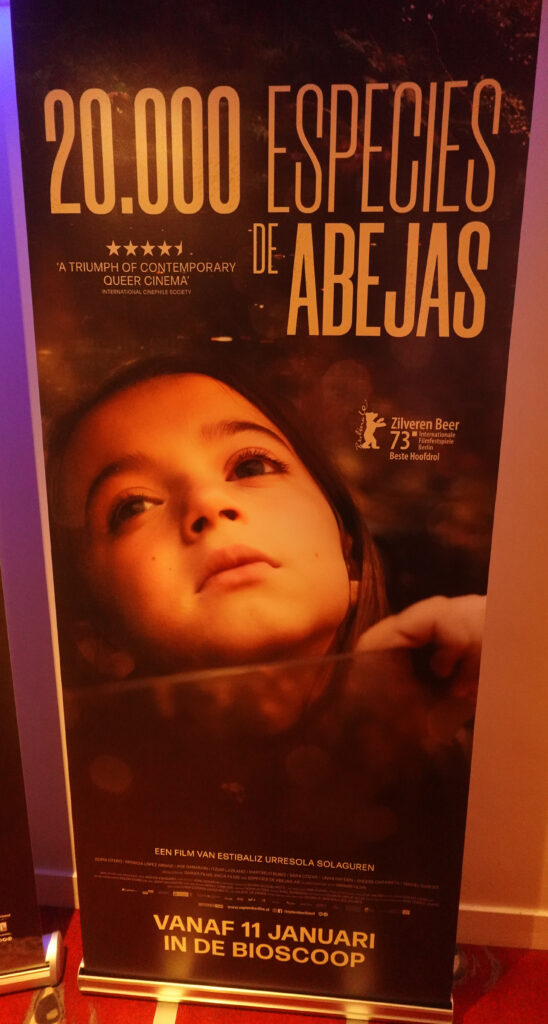

20.000 Species of Bees contains one of the awesomest acting by a child ever captured on film. I’m not exagerating: lead actress Sofía Otéro, born in 2013, does such a magnificent job that she won the Best Actress Prize in Berlin‘s film festival and became the youngest artist ever to be praised with this award: yes, never before a 9-years-old actress took home a Silver Bear. Well deserved! I can’t remember any acting performance by an adult in 2023’s films that really stands a chance in comparison with the astonishings results achieved by Sofia.

It’s a drama so well-told and well-acted, a film so masterfully conducted, and yet it has the lightness of simplicity, no excessive gimmicks, no expensive special effects, no over-the-top proclamations. Its main virtue doesn’t lie in the technicalities of movie-making as a creation of thrilling sensations, but rather in the capacity of the medium to transform our affections. Cinema can be life-changing when it is able, through the means of instigating in us empathy, to transform the structure of affects of the audience in such a way that we may feel, upon leaving the screening, that our way of feeling about the world has been transformed for the better.

20.000 Species of Bees is one of those rare gems, that a philosopher such as myself always seeks and hunts for, that actually makes us wiser. It does so through the delicate, compelling, gently unveiling storytelling about a 8-year-old queer child, Aitor / Lucía. The first is the cis boy given name, the latter the trans girl chosen name. Aitor stands as the atribution of an “original” gender, and Lucía as the one transitioned towards. It’s quite a challenge to write about this film because of the minefield of language – we keep on stumbling on the binarity of the article he and she, and here we would need to refer to the person in question with something that explodes this binarity. I’ll settle, for now, with “the queer kid”.

A child’s curiosity and inquisitiveness is shown here in several occasions: on the boat, while looking for a lost/stolen statue that disappeared from the local church, the child discusses with the oldsters what is faith, if sirens exist etc. 20.000 Species of Bees includes several scenes where the queer kid acts as a philosopher, questioning those around him with very important and difficult inquiries – and it reveals its hidden psyche by the questions asked. Adressed at the brother, the question “when I was at mummy’s belly, did anything go wrong?” reveals the queer kid’s insecurity, it’s fear of being the carrier of a birth defect. The questions posed are relevant, and usually answers given back to the child are adequate, not dogmatically imposed with authoritarianism, but thoughtful – he’s the element of wisdom I’ve been talking about and I’ll further highlight.

The queer kid questions critically the religious rites around him/her, starting from baptism. The child wants to know what’s it all about those special waters that are used to wet the newborn baby’s head. The child is perplexed to hear that this ritual is destined to cleanse sins. A baby a few days old, with no moral consciousness, has already sinned? What the heck?!? We know that baptism is also a matter of name-giving. And the label they attach to us at the baptismal ritual comes gendered. What if later on I find out I don’t like what has been done to me in baptism? – asks the queer kid. What if a baby, when he grows up, hates the name it has been given and wants to change it? These sort of questions are in the crux of the film.

It also talks about divisions within the traditionad family between a majority of those who want to impose upon Aitor the performances and conducts of a boy, and a minority that can respect and learn to understand the process of becoming-Lucía that this child is going through. The mother here goes herselft through a transformation process, and ends up belonging to the minority that embraces queerness and treats it as precious. In contrast with the grandmother who refuses and despises the process that her grandaaughter is manifesting. The theme of the generation gap is clearly present here – the older woman is depicted as being conservative and transfobic, while the middle aged woman is more open-minded and cariñosa about the feminization of the person she used to refer to as her son. Three generations are involved in this heated controversy about fluidity of gender. The grandmother tries to convince her daughter she is not doing correctly the job of a mother, she’s becoming guilty of over-indulgence: the boy needs to be forced to conform to the norms and forms of masculinity!

There’s an oppressive mood in several scenes because of the presence of this discourse of conformity, of discipline, of gender binaries that should be dogmatically followed, as if human life, genderwise, had only two possible scripts at our disposal – you’re either a girl, Barbie-loving, wanting to parade in a pink dress, or a boy, Rambo-admirer, who chooses toys of masculine power such as soldiers and cars. Yet, this oppression is a heavy burden that the film suceeds to overcome and to lift through the generous light it sheds upon Aitor / Lucía through the conducts of cariño of those, like the mother and the “auntie”, that accept and cherish the existential transformation of the child, allowing different performances of gender than those expected to flourish.

I’ve left the screening feeling lighter, unburdened, as if the film managed to lift some weight from my shoulder: it’s because empathy here is the dominant affect, we are enticed into it by the mother-child relation facing the challenge of genre transformation in infancy. Thanks to the authenticity of the acting of everyone in the main roles, the audience gets a shot in the vein of the emotiond substance called cariño in Spanish and carinho in Portuguese, which in English would probably be best translated as tenderness or kindness.

At the end of this tale, the mother leads the way in empathetic behaviour rooted in cariño by displaying acceptance of the feelings and chosen ways of conduct of the human entity that is the fruit of her womb. The family party at the finale is highly memorable: before it, the mother dresses the queer kid as a girl, yielding to her desire: “quiero que me Ilames Lucía!” But the child, in its sensitivity to a probable offense this may cause to those that surround, decides to shift back to boy’s clothes, especially after witnessing and feeling the constant irritation and revulsion for her transitioning towards girlhood – transphobia manifestas extremely strongly in the father and grandmother, both of them examples of homophobia/transphobia justified in terms of “the boy is a boy, he will suffer too much if he goes on being a sissy” etc.

I love the finale of this film. Firstly, because the queer element gets ousted from the family photo. No one calls Airto to join the damn photo. The traditional family ocludes the queer element, it kicks out queerness to show the world a falsified image of itself. He/she chooses to go away from such confusing family gatherings and ventures into the woods. This film is not at all a thriller, but when Aitor/Lúcia disappears into the woods, a martyr of loneliness, suffering from isolation, suddenly the film gets very suspenseful. A child disappears into the woods and some might suspect of an attempt of suicide. Lots of voices walk around yelling “Aitor, where are you?”. But the call for the masculine name gets un-answered. The brother, and then the mother, decide to call out differently: “Lucía! Lucía!”

When the call for Lúcia starts to resonate, the film goes through a sudden change of light. It’s a call of comprehension of the other, of acceptance of its autonomy. A process that the “auntie” helps to produce – being, in my opinion, perhaps the wisest person in the tale. The peril of suicide clearly existed. The child was suffering from episodes of self-denial, low self-esteem (my toes are horrible! etc.). The queer kid was perhaps suffering from what psychiatrists would call “gender disphoria” and had asked auntie: “if I die, can I be reborn as a girl?”

I cherish the silence that follows this question: it’s here one of the place’s in the film where I find the honey of wisdom flowing through the family’s beehive. Adults should do it more often – be silenced by a queer child’s questioning. Be thoughtful and aware of consequences before uttering an answer. This brilliant scene shows how well the director managed to master the matter of rhythm. The effect of wisdom and cariño I’m talking about would be lost if the silence had been shorter, it the rhythm of the dialogue had been rushed. This is not only a very important moment in the plot, for the density of meaning in this human relation – it shows us all a way to relate to alterity, with respectful silence to the other’s discourse, followed by thoughtful and empathetic answer.

When we’re confronted with such piercing pieces of inquisitiviness coming from the realm of the queer, the abnormal, the divergent from the dominant gender-sex dogmas, we should act as the auntie acted. No rush. No moral condemnation. No authoritarian imposition, top-down, of a thou shalt. The answer is wise, cariñosa, filled with a notion of reality-as-perfect-as-it-is, and it might have saved a precious life. “You don’t need to die to become a girl, you’ve already become a girl, and a perfect one” etc.

The disappearance of the statue from the church also teaches some important lessons to the kid: my educated guess, here, is that the queer kid reads this as fragility of the so-called sacred. That means: there are people who dare to confront the sacred, to treat it in such a way as to desacralize it. What could be read by the conservative and the faithful as nothing but barbaric vandalism, for the queer kid can have other meanings, especially when we’re dealing with a kid that clearly admits to its desire: “when I grow up, I don’t wanna be like my father.” The kid that was baptized as Airto is clearly not fond of the father figure, and it’s obvious the mother who serves as the role model and also as the “nesting” parent.

The fact that the stolen statue was masculine and that a female statue still stands inside the church is also significant. Also the fact that the journeys done in search of the masculine statue in the boats don’t end up well – the male statue is not retrieved, the “sacred object” has in fact disappeared. The traditional shrine will not be replenished of its masculine figure. Maleness here occupies the space of a vacuum, of a fading influence, and we might go so far as to say that masculinity here smells badly, stinking of rigor mortis rigidity.

In the eyes of the Patriarchy, and also in the eyes of Theocracy, to transition away from your given-gender, towards your new gender, is always some sort of heresy. In the eyes of religious people, which more often then not are also the parrots of the patriarch’s slogans and dogmas, transexuality is a sin, a damnable heresy, a deviation to be punished, an error to be corrected. Faith is often a terrible breeding ground for homophobia, and I’m convinced that atheism and agnosticism may be better soils for the flourishing of queer-friendly societies.

The film clear shows how the god-idea gets amidst this mess: the more religiously minded are prone to see queerness as sin, and to judge gender fluidity as dangerous. Several characters voice transfobia and criticize the mother for being indulgent with the boy’s feminine manners. It’s the ideology that gets implanted into most of us to convince us to remain stuck in the gender and the name attributed to us at birth, because any queer deviation that you might indulge in might result in this: you’ll be doomed to hell. “Remember Sodoma and Gomorrah!” ideology and affect-structure.

What I mean is this: a myth such as Sodoma and Gomorra has been justifying intolerance and rage for centuries against sex-gender dissidents – and it’s quite a shame that so many people still consider it “sacred” and remain stuck in conducts of hateful homofobia and transfobia because it’s supposedly ordained in a Sacred Book.

The whole swimming pool issue is also worth some remarks. Well, the queer kid doesn’t want to go swimming with the other children – it may seem a minor affair, hardly worthy of kinematic suspense. But 20.000 Species of Bees builds the theme quite beautifully and brilliantly. It’s clear that the queer kid doesn’t suffer from hidrophobia – there’s scenes that the joyous interaction of the body with water is clearly shown: Aitor / Lúcia is open to the joys of swimming.

What’s troublesome for the kid is this: going into the boys changing room, when you feel much more like a girl; and yet you wouldn’t be accepted in the girls changing room, especially in a situation where genitalias are exposed. It’s hard to get inside the girls’ room without causing havoc when you have a penis. That scene is so bittersweet: the mother indulges and yields to the child’s desire to be taken to the girls section; the kid sits to piss, while the other girl asks why; and the mother replys: “boys also piss seated…”. A mother-and-child fight follows. The queer kid, still being called Aitor, takes the decision to state his will power: “he” doesn’t want to be called by that name; neither he wants anymore the nickname Cocó (which at least is gender-neutral); he neither wants to be referred to as chico. A whole existential process leads up to the manifestation of desire conveyed by “I want you to call me Lucía”.

20.000 Species of Bees is a sort of summer-vacation Bildungsroman of a coming-out-of-the-closet by a lovely queer kid: from now on, she wants to be called Lúcia, and she wants to dress as a girl, and she won’t see the father as role-model. The queer kid has decreed it will be sculptor of her own flesh and treats it like beeswax. The fact that the mother is an artist working with matter which can be treated, at least partiatly, as something fluid and plastic, is another interesting factor here, deserving the interpretation of semiotics.

Fast learner, the queer kid has knowledge recently gained about the diversity of bees and about the fact they can be doctors – while previously seen as dangerous and potentially harmful. What was feared can now be embraced. But this queerness, this gender transition, this acceptance of fluidity, can only flourish and turn into honey in a context of wise relationships, inside a web of affects where cariño, and not hatefulness and rigidity, is the invisible stuff that reigns.

To conclude this piece of praise for a film I’ve truly loved watching, and that is growing on me after the screening, I was content to discover that the story’s first seed came from a real life event concerning <Ekai Lursundi>, as <The Guardian reports>:

“Estibaliz Urresola Solaguren first had the idea for making her debut film when she read about the suicide of a 16-year-old trans boy in the Basque Country where she lives. What struck her about the case was the hopeful note that the teenager left behind, imagining a kinder, more accepting world. “He said he was making this decision to shine some light on people in his situation, for visibility. He was accepted by his family, but he was suffering a lot. It’s very sad.”

When Solaguren first had the idea for the film back in 2018, and approached a local support group for trans children and their families, it turned out the family of the 16-year-old boy who killed himself were members. At the beginning, she didn’t try to speak to them. “I didn’t want to look like a person trying to benefit from their pain,” she says. “To be like, ‘That happened. Here’s a story.’ I didn’t want to do that.” Besides, the film she had in mind was not his story but rather the kinder world he’d hoped would be his legacy. “I want to make a luminous, bright film. So trans kids also could have a healthy reference. Not [a character] who would suffer or die or be a problem for their families.”

This explains a lot: this film may be aesthetically realist, naturalistic, very grounded in reality, and yet there’s some sort of utopian mood here. It’s because the filmmaker tried to capture the kinder world, different from ours, where a gender transition could have suceeded instead of collapsing; in other terms, in reality the sad ending was a suicide (Ekai Lursundi didn’t survive), but in film the somewhat happy ending of Airto/Lucía will stand as a symbol of the reign of a wise cariño.

I don’t usually appreciate happy endings, and often feel quite suspicious when they happen cause my nose denounces the stink of wishful thinking and self-blinding through irrational consolation prizes. But 20.000 Species of Bees sent me home feeling so well that I still feel, for this film, that rare gratitude that may be expressed as thus: you have depicted for me a wiser world, but you haven’t lied about the difficulties and challenges of getting there. Watching this has made me wiser and hopefully it will be the benefactor of many other people whose sensibilities, if they open themselves up to this tale, will learn gratefully how, despite all odds, the threat of suicide might be vanquished by cariño‘s wise, tender measures.

Eduardo Carli de Moraes

A Casa de Vidro

Film seen in Amsterdam’s Cinecenter, January 13th 2024

FURTHER READING: Attitude – Variety – The Guardian.

SHARE ON SOCIAL MEDIA:

“20.000 Species of Bees”, a new masterpiece of Queer Cinema, invites us to see gender fluidity through the wise lens of cariño. A film by Estibaliz Urresola. Read at @acasadevidro: https://t.co/wXOHoxto7X

— A Casa de Vidro (@acasadevidro) January 17, 2024

Publicado em: 16/01/24

De autoria: Eduardo Carli de Moraes